PDFLINK |

Mary Wheat Gray: “I Never Give Up”

Communicated by Notices Associate Editor Richard Levine

Introduction

Mathematician Mary Wheat Gray received a law degree, taught herself statistics, and became the “mother of us all” 5 for her work to advance women’s and human rights. With the new Mary and Alfie Gray Award for Social Justice, established by the Association for Women in Mathematics, we decided it was time to take a more personal and reflective dive into Dr. Gray’s life and career. We interviewed her to see what more we could learn from her story.

Mary Gray is a mathematician, attorney, and statistician. She is highly decorated, the most recent of her many awards being the Elizabeth L. Scott Award from the Committee of Presidents of Statistical Societies (2012) and the American Statistical Association Karl E. Peace Award for Outstanding Statistical Contributions for the Betterment of Society (2017). American University recently promoted her to the prestigious rank of Distinguished Professor (2019).

Known for crashing a meeting of the American Mathematical Society after confirming in the by-laws that these were open meetings, Mary was told she was not welcome. She was told this was because there was a gentleman’s agreement that the meetings were closed. She famously replied, “I’m not a gentleman; I’m staying” 17.

In 1971, the Association for Women in Mathematics (AWM) was founded, and Gray became the first chairperson 4. The AWM is now “the leading national society for women in the mathematical sciences” and plays “a critical role in increasing the presence and visibility of women in the mathematical sciences” 5, 3.

Between 2000 and 2018, Mary was elected as a Fellow of six organizations: Washington Academy of Sciences, Association for Women in Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Mathematical Society, American Statistical Association, and Association for Women in Mathematics. All of these Fellow awards are highly coveted and rarely given. For example, the American Statistical Association awards this highest honor to only up to 0.3% of its members. Mary’s ASA Fellow citation read: “For outstanding contributions in encouraging women and minorities in the study and practice of statistics and mathematics; for leadership in the applications of statistics in the field of human rights and litigation; and for statistical services to developing countries.” Mary was also elected to the International Statistical Institute.

Early life

Mary Wheat Gray (born April 8, 1938) was born and raised in the busy, small town of Hastings, Nebraska. It is a place where people come to experience the magic of “one of the greatest wildlife spectacles on the continent,” where annually 80% of the world’s sandhill cranes and 250 species of water fowl migrate 16 . . . and where mathematicians come to model it.

Mary has deep roots in Nebraska. One grandparent emigrated there from Germany, and three others were born there. Her father, Neil Claude Wheat, was manager of a trucking firm, after earlier holding jobs as a policeman, truck driver, and mechanic. Her mother, Lillie Alves, was a cafeteria worker, after earlier being a schoolteacher and homemaker.

Mary’s parents had strong values for education and encouraged her to learn. At home, they taught Mary history, sparking a lifelong interest in the subject. Also, her father began asking her mental arithmetic questions when she was only five years old, sparking her love for mathematics. It is no surprise that the subjects Mary enjoyed most while attending Hastings Senior High School were mathematics, history, and physics.

In high school, girls had to take sewing instead of mechanical drawing, so Mary did experience some gender discrimination. She said, “I’ve always, when I taught a lot of calculus, blamed the fact that I couldn’t draw very good diagrams on the board to the fact that they never let me take mechanical drawing. Of course, I never learned how to sew very well either. I took all the math that was available. My parents were supportive. All the teachers were supportive. So aside from not learning how to draw good pictures, I did fine [in high school].”

Hastings is also a college town, being the home to Hastings College. It is a highly ranked college: in the U.S. News and World Report’s 2022 Best College rankings, it ranks 17 out of about 90 Midwestern colleges. With a good college right on her doorstep, Mary decided to go to school there, and her talent for mathematics was recognized.

Mary graduated summa cum laude from Hastings College in 1959, with majors in mathematics and physics. Hastings College mathematics faculty member Dr. Jim Standley suggested she continue her studies in mathematics in a graduate program. She decided this would be her path. Many years later, Hastings College did not forget her. In 1996, they gave her a Doctor of Humane Letters, honoris causa.

Later, Mary received the same award (Doctor of Humane Letters, honoris causa) from Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts (2008). In addition, she received the Doctor of Laws, honoris causa, from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln (1993).

Early international experience

But first, Mary decided to broaden her horizons. Colleges like Hastings promote international study experiences, because they aim to provide broad intellectual experiences for their students. Mary applied to the Fulbright U.S. Student Program for study in Germany, which filled a “gap” year between her undergraduate and graduate study. This Fulbright program aims to develop cross-cultural academic connections that expand the perspectives of participants 19.

The Fulbright experience was a big move for Mary, because previously her only international experience had been a one-time crossing over the border to Canada from Detroit. The experience was what she called “a great revelation,” and it was the beginning of her international orientation which has led both to her pleasure and to her impressive body of international work that we will describe later in this article.

Mary used her Fulbright fellowship to study mathematics at the J.W. Goethe Universität Frankfurt. She received some good mathematics instruction there. A bonus was that National Medal of Science winner Saunders Mac Lane was in residence, and the leading mathematician at the university in Frankfurt was a woman. Mary reflected: “certainly I picked up other stuff—like the German version of the history of WW2—but the grant was to study math and that’s what I did.”

This experience centrally located Mary in Europe, and she got to travel a lot. The university she was studying at had an office that facilitated travel within Germany and all-around Europe. They wanted to show off Germany and Europe, and she was able to use their services. Mary met a lot of German students, and other people on her travels. Mary summed up her experience by reflecting that the Fulbright was also a positive experience “from the point of view of learning about other people and how to get around on your own and all kinds of things.” She told us: “It changed my entire perspective and made me very anxious to travel and to meet people in all sorts of places from then on. My life was definitely changed.”

Not many people in STEM fields apply for such experiences between undergraduate and graduate study (a “gap year”). STEM students don’t apply, according to Mary, because they “are afraid they’ll get behind and lose a year. And all too frequently, mathematicians don’t have another language besides their native language, or if so, it may not be one that’s usable under a Fulbright grant.” Most of the people who study on student Fulbrights are in the humanities or the arts. So the Fulbright is an important opportunity for STEM students. Because it was unusual that Mary came from the Midwest and wanted to study mathematics, it was not that hard for her to get a Fulbright grant.

Mary said that now she encourages students to “think a little bit larger,” and doesn’t necessarily think that they have to immediately go to graduate school. Mary said she intends to encourage more students to pursue this type of opportunity.

Higher mathematics education

Mary decided to do her graduate work at the University of Kansas. She earned an MA (1962) and a PhD there (1964), both in mathematics. Mary financed her studies with National Science Foundation and National Defense Education Act fellowships, employment as an assistant instructor at the university, and summer employment as a physicist at the National Bureau of Standards. Her dissertation was on Radical Subcategories 13. It was supervised by William Raymond Scott, an expert in group theory. Scott had 21 PhD students. Mary was the most prolific of them, having 34 PhD students of her own. Mary published this work on radical subcategories a few years after receiving her PhD.

Students in the doctoral program in mathematics at the University of Kansas had to demonstrate proficiency in two languages other than English. Mary declared, “Having just gotten off the boat, so to speak, from Germany, my German was pretty good. But I then met my future husband, and we both decided to take Russian, and we learned enough Russian that we could handle Russian mathematics and maybe a little bit more.” Mary told us that her language advantage helped her to get along with everyone, including the faculty.

But all was not ideal in graduate school. At the time, Mary was the only woman in the PhD program at the University of Kansas. The only other woman to get a PhD there in mathematics had done so 30 years prior. That woman was working in the department, but teaching in a “rather subsidiary role.” There were quite a few women in the beginning graduate courses, in the master’s degree program, and pursuing mathematics education, but there were no other women in the advanced mathematics courses that Mary took.

In graduate school, Mary experienced her first discrimination for being a woman in mathematics. In her words: “I had never really encountered much discrimination at all as an undergraduate, nor in Germany. It was a revelation when I got to graduate school in Kansas, on the other hand…” Mary explained: “On my first day in graduate school, I had a course in a subject which I had not had as an undergraduate. At the end of class, when I was walking out, the instructor said to me, ‘You know, I don’t know what you’re doing here. You’re occupying a perfectly good position that could be filled by a man.’ I was very taken aback, having come from my undergraduate school and from a year in Germany where I hadn’t seen any of this.”

Mary agreed that this attitude was common at the time. The expectation was that women would be in the master’s, not doctoral, programs. “Maybe to work very hard, but not have much insight into mathematics as a subject matter,” Mary explained.

Married women then were expected to stay at home and take care of the family, so seeing a woman studying to be a professional was, as she put it, “totally beyond their general comprehension.” Mary continued to explain: “Since there was only one of me, I wasn’t threatening anybody…matter of fact, it’s only when they see people taking their jobs that people get worried about women or get worried about people from different backgrounds. As long as they’re just cooking dinner and cleaning the house, you know, they’re fine.”

Then Mary described what she did about her early experiences involving discrimination: “You know, my motto is: Don’t get mad, just get even. I decided to do better than everybody else in the class. The most interesting part is that many, many years later, when I would encounter this instructor in a joint mathematics meeting or something like that, he would always act as if he’d been my mentor and had contributed to my great success…And, you know, I could have said you’re a jerk ‹laughs› but I figured, well, he’ll have more women students and maybe he’ll learn and treat them a little bit better.” Mary continued: “While not overly enthusiastic, I was always very pleasant and encouraging to the men.”

Professorships

Mary met the love of her life, mathematician Alfred Gray (1939–1998), when both were in graduate school in mathematics at the University of Kansas. Alfie moved to the University of California, Los Angeles to complete his PhD in differential geometry.

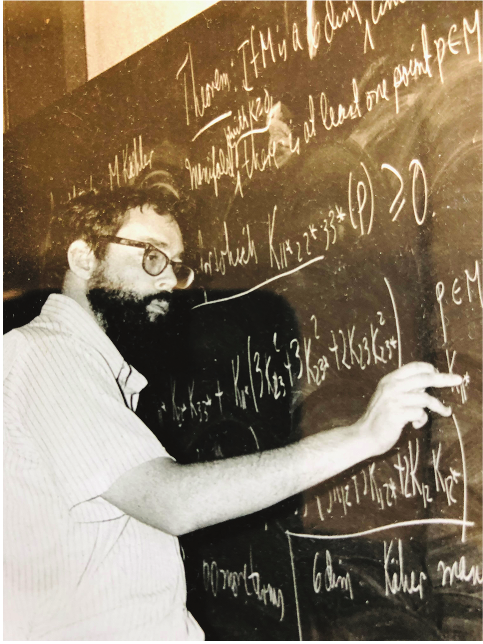

Alfred Gray at work.

Mary and Alfie married after graduating and became part of a dual-career couple, with the need to find two academic positions in the same geographic location. Their long-term strategy was to find a place “where there were two reasonable universities… We decided long ago we would probably never stay married if we were in the same department,” Mary explained.

The couple’s first move was to Berkeley, in 1964. Alfie took a post doc position at the University of California, Berkeley. He spent four years there. Mary taught a course in the Berkeley mathematics department in the summer (1965). Then Mary moved to a faculty position at the California State University, Hayward, which is now California State University, East Bay. Mary was on the faculty in the mathematics department at Hayward for three years (1965–68).

Their second move was to the Washington DC area, in 1968. Mary took a faculty position at American University and Alfie took a faculty position at the University of Maryland, College Park. The couple lived between their two places of employment so as to split the commute between them. Because they liked to travel, the idea of living in DC was attractive to them because there were lots of good universities and lots of nonstop flights to Europe.

Mary spent the rest of her career at American. She rose through the ranks to become a tenured full professor in the Department of Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science, which became the Department of Mathematics and Statistics. She was appointed chair of the department in 1977. Mary had this to say about her career opportunities: “I generally have felt that I got the position I was asking for in most cases, although sometimes it was a battle…sometimes I had to go out of the way to have this happen. Sometimes I haven’t gotten what I thought I should get because I was a woman. For example, it was only recently a few years ago that my university made me what’s known as a distinguished professor, which is a very rare category. There were only six or eight in the university as a whole, out of 800 faculty, something like that.”

Alfie spent the rest of his career at the University of Maryland. He made broad contributions to differential equations and complex variables, and specific contributions to classifications of types of geometrical structures. Mary reflected on Alfie: “He had an extraordinary ability to spend a period of time with differential geometers, or potential differential geometers, engage in joint work and establish ongoing productive collaborations, particularly with mathematicians in Spain, Italy, and Eastern Europe, when such engagement was not easy. His ability to learn languages was remarkable. At a memorial conference after his untimely death in Bilbao—where he tackled even Euskara—I learned the extent of his productive mentoring and our shared commitment to extending the inclusivity of mathematics.” Alfie died from a heart attack on October 27, 1998 at age 59 while working at 4 a.m. with students in a computer lab at a college in Bilbao, Spain. Two years later, there was a conference on differential geometry held in Bilbao in his memory 6. Mary added: “Alfie’s too-short career was marked with our common commitment to mathematics and social justice.”

Mary reflected on the topic of awards going to women. She gave an example where, in an academic unit, about half of the awards went to women. But the people who presided at the awards ceremony—the people who introduced the program, called out the winners, and handed out the awards—were not half women. “They could have had a lot of different people handing out the awards,” Mary observed. “There should be just as many senior women as senior men speaking. Women are perfectly capable of handing out an award,” Mary insisted. The lesson is that we need to be vigilant about correcting these inequities. We need to speak out about them, if we are to change them, even at the risk of embarrassing people. And we need to speak out about them repeatedly…we need to keep reminding people, because “they don’t remember,” Mary said.

Law school

After a fruitful career start in mathematics, Mary went back to school to study law, and she studied law through the 1970s. She used her faculty benefits to pay part of her law school tuition and fees. Her benefits included payment for two courses per semester.

On why she went to law school, Mary said: “Before taking on the world, I discovered that sometimes social justice begins at home.” She had gotten a statement about her work-related retirement benefits. From it, she learned that a man of the same age and with the same amount of accumulated funds would get 15% more per month than she would at retirement. “To my indignant complaint to the insurance company about discrimination in employee benefits on the basis of sex being illegal, the agent asserted that this was not discrimination on the basis of sex but rather on the basis of longevity.” Mary continued: “So, then I asked for a guarantee of longer life, and he accused me of just not understanding statistics. But I worked very hard with attorneys who were handling the case putting together data to back up the notion that in fact what they were doing was discriminatory. Then the insurance company accused me of not understanding the law.”

“I fixed that one by going to law school,” Mary said 11. She graduated with her Juris Doctorate (JD) summa cum laude from Washington College of Law in 1979. She is a member of the District of Columbia Bar, the US Supreme Court Bar, and the Federal District Court Bar, District of Columbia. This means she is able to practice law in the District of Columbia and before the Supreme Court.

Learning statistics

Mary learned statistics less formally by attending various seminar series and asking others for guidance on books she was reading. When asked about her education in statistics, Mary explained that she just “fell into it.” People kept approaching her and asking for her help on things that involved basic statistics:

There were a couple of questions—way back in the late seventies or early eighties…in the early feminist movement—that involved selection of White House Fellows. A question was: Why weren’t more women chosen to be White House Fellows? Someone wanted to look at the probability of the selection turning out the way it was, given what was known about the people who had been applicants for the position. They were looking for a mathematician and a statistician, anybody they could find who could calculate a probability and was a welcome co-conspirator in whatever it was they were doing.

I started on things like that. One thing led to another, and before long I was consulted on various things. There was another question about how these people were conducting the draft lottery. I decided that I better do some in-depth background checking on the issue, because my background wasn’t that strong. That’s the nice part about Washington DC. There’s an endless series of talks going on. The Census Bureau has a series. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has a series. A couple of the other agencies have various series going on. There are not-for-profit companies. So, you can always find something to go to, and you can always find somebody to help you out. If you need to pick a textbook and have no idea, there’s somebody—well, usually three or four people who will tell you different things, but at least there’s somebody—to guide you along. I don’t think I could have done [the advocacy work] without the facilities that Washington presented. Not to say there might be other places, either in a city with many agencies or in a place with a large research university, but it’s not something that you pick up that easily on your own.”

Today many people understand the value that statistical and mathematical knowledge can bring to the justice system, as evidenced by a number of commentaries and books on the subject (e.g., 7).

Which books or articles have been especially helpful to Mary as an attorney who regularly uses statistics in the practice of law? Actually, Mary recommends “that they sit in on a beginning graduate level stat course in a stat dept (and/or persuade their alma mater to offer such a course). Any attorney will realize that the changing scene of the law is accompanied by a changing scene of which statistics are useful; the subtleties are such that what is in writing at a given time is of limited use—as we tell students, a basic understanding is essential. However, the Finkelstein and Levin text is still good—but scares lawyers (and statisticians too).”

What law text(s) would be helpful to a statistician/expert witness? Mary pointed out that Harvard University, New York University, and Columbia University, among others, have first-year guides for law students that are helpful in explaining the topics and the way law study is organized.

Even well-educated lawyers in our highest courts struggle to fully understand data presented in law cases, and few seek their own further education to fill the gap in their knowledge. Mary was a true pioneer in this area, and she deserves credit for creating a path that others should follow. Her focus on understanding statistics to provide credible legal evidence has surely influenced a new generation of lawyers who followed a similar path to broaden their education beyond the legal field into statistics. Without more students willing to seek such education, however, legal decisions, even in the highest court, might be made without a full understanding of the evidence 18.

In her eighties and suffering from arthritis and other problems, Mary still finds energy to be an active participant in law and statistics. She regularly pens a column for Chance, a nontechnical magazine published by the American Statistical Association and Taylor & Francis Group that highlights the application of sound statistical practice (https://chance.amstat.org/about/). Her columns include “The Odds of Justice,” “Statistics Go to School and Then to Court,” “Who Gets to Vote?”, “Whom Shall We Kill? How Shall We Kill Them?”, and “Alexa Did It!” These columns discuss complex legal issues involving the use of statistics to make solid arguments. Mary notes: “Believe it or not, these [columns] are very hard to write, because you want to write something that both lawyers and statisticians will be happy with when they read it, and will maybe learn something from as well.”

Mary’s unique ability to find connections between the seemingly disparate fields of mathematics, law, and statistics undoubtedly impacted her career trajectory and success in facilitating change. With her big-picture perspective and varied skill set, she was able to argue for change in human rights, including women’s rights, which we discuss later.

Katerina Nesvit, data scientist, Marymount University (Arlington, VA), from Kharkiv, Ukraine—in the US for a little over a year—and Kristina Crona, mathematician, American University, originally from Sweden, with Mary Gray.

Federal testimony

Mary has testified on a variety of issues. These have included inequity in social security, pension, insurance, and pay; income tax reform; affirmative action; age discrimination; women and the military; and constitutional rights to travel. She has testified in front of a variety of federal committees. These have included US House committees: Ways and Means, Energy and Commerce, Education and Labor. They have also included US Senate committees: Human Resources and Labor, Commerce, Education and Civil Rights. Mary’s efforts were always to change the law to make it more equitable, and statistical evidence has always been the centerpiece of Mary’s testimonies.

Mary had this to say: “All of the testimony has involved statistics in one way or another, rather than necessarily anything legal. Usually what we’re trying to do with the testimony is get the law to be changed. Take income tax reform as an example. It didn’t used to be that you had a way to file a joint return if you had two incomes. And that was costing employed women a lot of money. So, the idea was to change the rules in order to make [tax law] more amenable to two-income families. The affirmative action is, same old, same old, let’s train more women and then hire them. The age discrimination, that had to do with the pension issue and the fact that there was a discrimination in pension…The point is that the law needs to be changed because you can show through statistics that the law is not treating people fairly.”

Most of the issues that Mary worked on involved gender in some way. Social security and retirement issues involved gender. Mary also worked on civil rights issues that involved race, and on constitutional rights that involved everyone. Which testimony had the most impact? Mary thought that making social security issues less gender discriminatory for two-career couples, divorced spouses, and employed wives ultimately had the most impact, because it affected the biggest portion of the population.

Mentoring

Mary has been a caring mentor to many students, faculty members, and other kinds of people who have crossed paths with her. The American Association for the Advancement of Science recognized her superior mentoring and guidance in 1994 in the form of a Mentor Award for Lifetime Achievement. This award recognizes Mary’s “extraordinary leadership to affect the climate and increase the participation in doctoral science education of individuals who are from underrepresented groups” 1.

In 2001, Mary received another national mentoring award: A Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Mentoring established by the White House and administered by the National Science Foundation. This award recognizes that Mary has been generous as a mentor to many individuals—both women and men—in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). She has especially encouraged promising women to major or pursue higher degrees in mathematics, guided many as they pursued their degrees, and given useful career advice.

Mary educates and engages her students in important world issues as part of their coursework by involving them in data collection and analysis for her projects. One such student was a faculty member who retired from the law school at American University and entered one of Mary’s graduate courses in statistics. Mary recalled: “She said she’d heard all these cases all the years that she’d been a practicing attorney, [but] she never understood what they were talking about [when it came to statistics]. So now she was coming back and taking graduate work in statistics. She did very well. Once she got her hands on statistics, she turned out to be good at it. I got her to do some nice volunteer work where she could use both her legal knowledge and her newly acquired statistical knowledge.”

When we asked Mary about her mentoring style, she said: “Because I don’t have children, I’ve probably always looked at students a little bit differently than a lot of people do. I’ve had a lot of PhD students, but I’ve also had a lot of undergraduate students who I’m still in touch with after many years…It’s probably the trait of looking out for other people. You’re worrying about: Why aren’t they doing what they should be doing? Couldn’t they make a little bit better use of their talents than they’re making? Are they about to make a bad choice? Sometimes they are about to make a bad choice in choosing a life partner. I always say to women in math that the best decision you often have to make is choosing a partner…There’s not a lot you can do in advising people except maybe leading them through some of the pitfalls that they may not have seen. So that’s what I look in on. What can we try to do to say that they’re making the right decisions, not only about their careers, but where it’s leading them.”

Mary has also supervised 34 dissertations and 11 master’s theses or projects. In addition, she has served as a member of many PhD dissertation committees, most in mathematics education.

American Association of University Professors

Individuals have benefitted from Mary’s mentoring, but so have organizations. Her volunteer work is extensive.

Mary has had a particularly strong affiliation with the American Association of University Professors (AAUP). This organization fits Mary’s professional outlook. It is dedicated to “advancing academic freedom and shared governance; defining professional values and standards; promoting the economic security of those who teach and research in higher education; organizing to make our goals a reality; and ensuring higher education’s contribution to the common good” 2.

For many years, Mary was chair of the AAUP’s Committee on Women, known as Committee W. Today the committee is merged with another committee into the Committee on Gender and Sexuality in the Academic Profession. It works to “formulate policy statements, provide resources, and report on matters of interest … addressing such issues as equity in pay, work/family balance, sexual harassment and discrimination, Title IX, and the role of gender and sexuality in rank and tenure.”

While Mary was chair of Committee W, it partnered with AAUP’s Committee on the Economic Status of the Profession (known as Committee Z). They recruited and oversaw the work of statistician Elizabeth L. Scott to develop the Higher Education Salary Evaluation Kit. The Kit was highly influential in raising salaries for women across the county so that they would be equitable with men who had the same background and experience. For details, please see 8. Mary identifies Elizabeth Scott as her biggest professional hero.

In 1979, Mary received the Georgina M. Smith Award from the AAUP. The award is presented to an individual who has improved the status of academic women or advanced collective bargaining in the profession. This award is not given on a regular basis, but only when someone especially deserving is identified as exceptionally outstanding as to merit.

Left: Mary Gray, mathematician Jair Koiler, and friend Rosa Maria in Rio de Janeiro. Right: Mary Gray at the Teatro Colon Buenos Aires in summer 2018. Photograph taken by mathematician Jair Koiler from Rio. Koiler is one of the mathematicians with whom Mary went to Uruguay years ago to get dissident mathematician Jose Luis Massera out of prison.

Leadership and diversity

In the 1970s, an academic department chairpersonship was not considered a desirable position in the mathematics department at American University where Mary was a professor. As a result, the role was rotated among the faculty members in the department, and Mary served as department chair six times (1977–1979, 1980–1981, 1983–1985, 2001–2003, 2009–2011, 2016–2018). Female mathematicians, especially those who held leadership positions, were not common at the time. Even today, fewer than 30% of department chairs in the mathematical sciences are women 9.

When asked if there was something different about women as leaders, Mary had this to say: “I think it’s difficult and probably unfair to make generalizations, but I think women are brought up to be more considerate of how they’re affecting other people. No matter how evolved a family they grew up in, they probably have been treated a little differently than sons in the family, or they’ve been expected to look out a little bit more for younger children, or when dad comes home from work, they’re the ones who produce the drinks or whatever. I think the training tends to be more to look out for others, and that probably carries over into the way people behave as department chairs. You can of course come up with exceptions. But I think if there’s one attribute, that would be it.” Mary’s thoughts are consistent with some of today’s business leaders, who note that inclusivity, empathy, and emotional intelligence are among the many reasons women make great leaders.

Mary has noticed that often there is diversity in only certain strata of the workforce. Therefore, she advises people to review the diversity and benefits of the full workforce of an organization. Expanding benefits, especially offering free tuition, is one of the best ways to improve diversity overall.

Mary remembered that perks—like the kind American University offered to her as a faculty member and that she used to finance her law school studies—can be useful to diversify a workforce. Mary found this way: “The university is always talking about how we need more diversity. We need more diversity, they say, and then they don’t want to do much of anything. To have more students, particularly from African American and Hispanic communities, at American University is going to be difficult. One thing that we did—and I spent weeks and hours and months on this—was get American University to give their employees free tuition for their kids. And that’s good.”

But what about contract workers, Mary wondered. Can’t their kids get free tuition too, and at the same time help to diversify the student body? Mary continued: “Not everybody who works at the university is an employee of the university. The people who do the cleaning and the cooking are contractors. They’re not actually employees, so their kids didn’t get free tuition. Well, almost everybody on the cleaning staff is Latino and almost everybody on the cooking staff is African American. And so, you know, it’s a perfect place for diversity…I finally managed to get the university to agree to provide free tuition for the children of all of the subcontracting workers, as well as some benefits for the workers themselves. This opens up opportunity for a vast variety of people.”

Mary realized that diversity would result only if a diverse group of people actually used the employee benefit: “You need to get out there and make the kids aware of it, make the parents aware of it…” And we shouldn’t make assumptions about the people who could use the benefit, because those assumptions might be racist. “Then the administration said the benefit was only for the elementary courses, like the writing courses and the elementary math courses. But think about the inherent racism of what they were saying. Well, I rounded up a worker who I knew, and the worker came to talk in the next meeting. We had the people in charge there and one of the workers said: I really want to take a graduate course in management because I’ve got five barber shops. And I would like to expand my knowledge and network in the management training. That shut up all the trustees immediately.”

Mary continues to raise the question herself as she visits other institutions: “That’s one thing: When I go to other universities and sometimes people say, ‘What can we do?’ The first thing I ask is: Who cleans, and who cooks? Are they real employees? And what are their benefits? And almost always it opens up opportunities for them. And there’s gender involved too, because almost all of the cleaners—or at least more than two thirds of them—are women.” Mary continues to be a tireless champion for increasing diversity.

Collaborative networks

We noted that Mary has built a huge network through which she gets asked to be involved in a variety of issues encompassing many states and countries. When asked about how she builds the network and partnerships, she had this to say: “It’s usually somebody different for everything. For this most recent insurance article, I corralled a retired insurance lawyer who lives in my neighborhood to help. For women in the military, I tracked down a woman who was a Colonel in the military. I’m always looking for somebody who knows more about [a topic] than I do.”

Also, Mary gets involved when there are calculations to be made. She noted: “The reason I’m involved in this labor dispute on campus now is because the people who are doing the union negotiation don’t like to have to look at numbers. I think people are not as well informed as they might be, and it’s not only with the advent of Facebook and other social media. The traditional media that you and I grew up on is not pursued by enough people.” That’s why Mary’s department created an elementary statistics course that would be useful for improving the statistical literacy of the masses. She said: “We call it, ‘Read the New York Times,’ because that’s about as deep as they get into the statistics. If people would keep track of the issues that come up, then when it impinges on something that they might know something about or might be interested in, there’s a way they can seek more information. Reading the newspaper is an old-fashioned way to get connected, and it still works.”

How does Mary get her information about current events? She always listens to the news while she is driving to work: “It’s a drive that varies from just under 15 minutes to just under 30 minutes, depending upon the traffic and which day of the week it is and so on. That’s just enough time to get the morning news. American University has a public radio station called WAMU, and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) news comes on at nine o’clock in the morning. So, I usually get a few minutes of US news from WAMU, and then at nine o’clock BBC switches in, and then I arrive at work at nine fifteen. I get a little bit of all of it.”

Networking is an essential career element, including in the mathematical sciences. If networking doesn’t come naturally to people, they can always intentionally learn to do it by—among other things—concentrating on their higher purpose, as Mary does. Since statisticians like Mary like to look at numbers, they can be of special use in networks that are formed to achieve a higher purpose.

International justice work

Mary has worked on many human rights issues across the globe: in the Palestinian Occupied Territory, Gaza, Iraq, Rwanda, the Middle East, and elsewhere. Her entry to this work has been through the mathematical societies. Also, she has worked with Amnesty International, and she is a member, former chair of the board, and an executive committee member of Amideast, an American nonprofit organization engaged in international education, training, and development activities in the Middle East and North Africa.

How did Mary first get involved in international justice work? Mary said: “The first case I got involved with was the mathematician who we got out of prison in Uruguay…I was doing the work as a representative of the American Mathematical Society, but I met people who worked in Amnesty International. And then I had a good colleague in the sociology department here at American University who was Palestinian. He got me interested in working on Palestinian issues, which of course never get resolved. Every day there’s another atrocity, but that certainly got me interested. And then from those organizations, I spread out to see what else I could work on.” Mary has made many radio and television appearances, and given many speeches, to the above-mentioned and other groups about a myriad of human rights issues.

Women’s rights

What is Mary most proud of, given her immense body of work? Mary said: “I think probably the work I’ve done on women’s rights. As a special part of social justice starting the Association for Women in Mathematics (AWM) and getting it up and running and seeing what it’s progressed to subsequently…Some of the legislation, particularly the pension legislation, which made a measurable effect upon people’s lives. So, gender and the sports, also the work in gender equity in sports. That I see has had a definite impact that lasts. Some of it we’ve lost, some of it we have to do again, but basically, it’s there. Some of the other human rights work, I’ve done a lot of death penalty work, which seems to be futile. Some of the human rights work and some parts of the world also seem to be rather futile. So, it’s probably the gender stuff that’s more easily measurable and has had a more lasting effect.”

Mary provided a roadmap about legal options for those who believe they have been discriminated against 12, 10, 14. Asked about the overall progress that’s been made for women in the profession, Mary said: “There’s been progress. It just hasn’t been enough…You would not know we have a vice president,” Mary said, noting that Vice President Kamala Harris has a visibility problem that women professionals often have. “Every time I read about people’s candidates for succeeding Biden, if he’s going to be succeeded, we don’t see anything about his woman vice president. Why isn’t it being considered? It’s exceedingly annoying.” Asked about what makes the US different from the UK, Germany, and the Scandinavian countries, all of which have had women in the highest political leadership position, Mary remarked: “I don’t know. I’m on some sort of email list for a company called Classic Firearms. The classic firearms that they advertise turn out to be North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) rifles that you can buy online for a couple of thousand dollars, or kits where you can convert your pistol to being an automatic weapon, et cetera. People at the university can’t seem to help me get rid of this. It keeps coming back all the time. The point is that it has an audience. There is an audience for guns like this. That’s the big difference I see between us and some of the other countries that are like us in other ways.”

Future work

What would Mary like to work on next? She said:

I’m still very interested in tax policy. It’s one of the things that I wanted to go into a bit more. There was an article in yesterday’s newspaper about carbon tax. The author was making a point that you need to solve environmental issues in other ways than tax policy. I don’t think that’s true. With tax policy, I don’t think you can solve all of the issues, but I think you can solve a lot of the issues that people aren’t thinking about. In some sense, tax policy is a backdoor in, but it’s an important backdoor because it’s where the money comes from, and it gets people’s attention.

One of my favorite issues with taxes is: Why is social security not collected on your entire salary; why does it stop after you get to a certain cut-point? This benefits people who are making a lot of money, and it doesn’t seem to me to be fair. It seems to me, if everybody who made a million dollars had to pay whatever it is, 6.9%, there’d be a lot more money in the social security coffers for people who are not so well off. That’s not suggested by Bernie Sanders. It’s not suggested by Elizabeth Warren. It’s not suggested by anybody. The question is, why not?

Everybody says that people won’t buy it. They won’t like it. Well, of course they don’t like it anytime people say to increase the taxes. So, I don’t think that’s a reason. One of the things I want to look into is whether there’s a limitation like that in any other country. The systems operate differently, but if you look at some of the Western European countries which have similar systems, I don’t think there’s any sort of similar cutoff issue. I need to get another research assistant, or I need to go get one of my friends in the economics department here to see what, if anything, he or she knows about it.

When asked how she deals with frustration, Mary said: “I feel that I need some distractions that are far removed from the problems of the world. I like to go to an opera. I like to read a book. I like to travel when it’s possible.” Sometimes Mary publishes reviews of plays (Arcadia; Calculus; A Disappearing Number), films (The Tourist; Agora; The Imitation Game; La Figure de la Terre; The Man Who Knew Infinity; Gifted) and opera (Dr Dee; Emilie), in addition to books. Many of her reviews were published in The Mathematical Intelligencer.

Mary continues to be involved in improving American University. The unionized staff went on strike at the beginning of the fall semester, protesting stagnant wages 15. Mary was in her office advising the strikers when it was time for us to meet for the final time on Zoom. She came to our meeting late, and she left early, in order to advise the strikers. “We will not give up,” one of the strikers was quoted as saying, apropos to describing Mary Gray’s career approach.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Mary Gray for the time she took to participate in interviews with us, conducted by Zoom, and to respond to email questions. We would also like to thank Ms. Denise Williams at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for preparing transcriptions of the Zoom interviews, which greatly facilitated our work.

References

- [1]

- American Association for the Advancement of Science, AAAS Mentor Award for Lifetime Achievement. Accessed on 8/30/2022 at https://www.aaas.org/awards/mentor-lifetime?adobe_mc=MCMID%3D49417266252237775264378133271987319173%7CMCORGID%3D242B6472541199F70A4C98A6%2540AdobeOrg%7CTS%3D1661883334.

- [2]

- American Association of University Professors. Accessed on 8/30/2022 at https://www.aaup.org/.

- [3]

- Association for Women in Mathematics, History. Accessed on 8/31/2022 at https://awm-math.org/about/history/.

- [4]

- Janet L. Beery, Sarah J. Greenwald, and Cathy Kessel, AWM Through the Decades: A Chronology of the First Fifty Years, in Fifty Years of Women in Mathematics, Chapter 1, Association for Women in Mathematics Series (AWMS, volume 28), Springer, pp. 1–7, 2022. Accessed on 10/31/2022 at https://sites.google.com/view/awm-through-the-decades.

- [5]

- Lenore Blum, A Brief History of the Association for Women in Mathematics: The Presidents’ Perspectives: Mary Gray (1971–1973): The mother of us all, Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 39 (1991), no. 7, 738–774. Accessed on 5/18/2022 at https://web.archive.org/web/20180213230938/http://www.awm-math.org/articles/notices/199107/blum/node2.html#SECTION02021000000000000000.

- [6]

- Marisa Fernandez and Joseph A. Wolf, eds., Global Differential Geometry; the Mathematical Legacy of Alfred Gray, Proceedings of the International Congress on Differential Geometry, Bilbao, Spain, September 18–20, 2000, American Mathematical Society, 2001. Accessed on 9/6/2022 at http://www.ams.org/books/conm/288/conm288-endmatter.pdf.

- [7]

- Michael O. Finkelstein and Bruce Levin, Statistics for Lawyers, Third Edition, Springer, 657 pages, ISBN-13 978-1-4419-5985-0, 2015.

- [8]

- Amanda L. Golbeck, Equivalence: Elizabeth L. Scott at Berkeley, Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press, 608 pages, 2017, ISBN 978-1-4822-4944-6.

- [9]

- Amanda L. Golbeck, Thomas H. Barr, and Colleen A. Rose, Fall 2018 departmental profile report, Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 67 (2020), no. 10, 1615–1621.

- [10]

- Mary Gray, Adjusting the odds, AmStat News, July 1, 2017. Accessed on 8/31/2022 at https://magazine.amstat.org/blog/2017/07/01/adjusting-the-odds/.

- [11]

- Mary W. Gray, 27th Distinguished Statistician Colloquium: Interview of Dr. Mary W. Gray, recorded video, Minutes 16–17, November 9, 2021. Accessed on 8/30/2022 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJhI05bLu-0&t=2084s.

- [12]

- Mary Gray, Leadership and the legal system, in Amanda L. Golbeck, Ingram Olkin, and Yulia R. Gel, Leadership and Women in Statistics, pp. 229–244, Chapman & Hall, 2016.

- [13]

- Mary Gray, Radical subcategories, Pacific Journal of Mathematics 23 (1967), no. 1, 79–89.

- [14]

- Mary Gray, Statistics as a tool for equity, in Amanda L. Golbeck, Leadership in Statistics and Data Science: Planning for Inclusive Excellence, pp. 221–238, Springer, 2021.

- [15]

- Liam Knox, School starts with a strike at American University, Inside Higher Ed, August 23, 2022. Accessed on 8/31/2022 at https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/08/23/american-u-staff-strike-higher-wages.

- [16]

- Nebraska Flyway, The Great Migration. Accessed on 5/23/2022 at https://nebraskaflyway.com/.

- [17]

- J. J. O’Connor and E. F. Robertson, Mary Lee Wheat Gray, MacTutor, last update November 2006. Accessed on 8/31/2022 at https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Gray/.

- [18]

- Oliver Roeder, The Supreme Court is Allergic to Math, FiveThirtyEight, October 17, 2017. Accessed on 8/30/2022 at https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-supreme-court-is-allergic-to-math/.

- [19]

- U.S. Department of State, What is the Fulbright U.S. Student Program. Accessed on 5/24/2022 at https://us.fulbrightonline.org/fulbright-us-student-program.

Credits

Opening images are courtesy of Amanda L. Golbeck and Madhu Mazumdar.

Figures 1–3 are courtesy of Mary Gray.

Photo of Amanda L. Golbeck is courtesy of Amanda L. Golbeck.

Photo of Madhu Mazumdar is courtesy of Madhu Mazumdar.