PDFLINK |

Mathematicians Confront Political Tests: The American Mathematical Society and the Red Scare in 1954

Communicated by Notices Associate Editor Laura Turner

“Five years after a world war has been won, men’s hearts should anticipate a long peace, and men’s minds should be free from the heavy weight that comes with war. But this is not such a period—for this is not a period of peace. This is a time of the Cold War. This is a time when all the world is split into two vast, increasingly hostile armed camps—a time of a great armaments race” McC50. So Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wis.) bellowed from the dais in Wheeling, West Virginia, in a Lincoln’s birthday speech in February 1950. But, in McCarthy’s view, it was even worse. “I have in my hand,” he told his listeners, “57 cases of individuals who would appear to be either card-carrying members or certainly loyal to the Communist Party, but who nevertheless are still helping to shape our foreign policy” as employees of the US State Department.

Although the process of rooting out communists had already begun prior to McCarthy’s speech, the Red-hunting mania that followed it in the 1950s was particularly intense. When four mathematicians—one in New York, two in Michigan, and one in Tennessee—lost their teaching jobs in 1954 for failing to answer questions about their political beliefs before different investigative committees, their plight came before an American Mathematical Society unsure of how far it could or should go in asserting itself in the political, as opposed to the mathematical, arena.

The Attraction and Peril of Communist Party Membership

The Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) (also called the American Communist Party) was founded in 1919 and was affiliated with the Communist International (Comintern) headquartered in Moscow. A legal party, it put forward state and federal candidates for election, including candidates for president between 1924 and 1940. One of the latter, Earl Browder, had three sons all of whom became mathematicians: Felix, long associated with the University of Chicago, William at Princeton, and Andrew at Brown. Though never attaining enough votes to win a seat, the American Communist Party nevertheless appealed to a portion of the populace as a counter to what was deemed the class system that had caused the Great Depression of the 1930s. The fact, however, that the Comintern publicized its purpose to lead a worldwide struggle for overturning non-communist governments, gave ample reason for monitoring the CPUSA. Many state and federal investigative committees—for example, the California Senate Factfinding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities (the so-called Tenney Committee named after the rabidly anti-communist state senator, Jack Tenney) and the Special Committee of the Board of Higher Education of the City of New York—were set up or went into action as the result of what was perceived as a growing communist threat. Their procedures, for better or for worse, appear largely to have been modelled on those of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (usually styled HUAC), which was established in 1938 and which set a certain precedent for how to go about purging the country of covert communist influence.Footnote1

There was an equally drastic reaction to the communist threat in the US for a period after the Russian Revolution, 1917–1920. A general account of the “second Red Scare” of concern here is included in Sto13, which acknowledges the different assessments historians have made of the overall harm done by the anti-communist investigations of the time. Relative to the impact of the second Red Scare on academia per se, see Sch86. Indeed, the literature on the period, on the roles of the FBI and HUAC in it, and on many other specific aspects of it, is vast. The Notice’s restrictions on the maximal number of references permitted per article has meant that we have been unable to direct our readers more fully to specific secondary sources.

Meanwhile, agents of the Soviet Union had infiltrated some of the most security-sensitive areas of the US government and military from at least the 1930s and had gone undetected for years despite the FBI’s vigorous efforts. Among the best known, Klaus Fuchs and Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were eventually caught and tried by the early 1950s for passing information on nuclear weapons development to the USSR. Members of Congress seeking to root out subversives of a different sort found it could also pay politically to have high profile influencers of American life testify either as informers, like Walt Disney and Ronald Reagan, or as suspected members or sympathizers of the CPUSA such as the group of film writers and directors known as the Hollywood Ten (Figure 1). Whether or not their suspects subscribed to the cause of overthrowing the US government, the argument went that, since communists were supposed to adhere dogmatically to the party line, they were a risk to the status quo.

The House Committee on Un-American Activities opened its televised investigation of communist infiltration into the professional, educational, and entertainment fields in Southern California on March 23, 1953. The chair is Representative Harold Velde. From left to right: Gordon Scherer, Kit Clardy, Velde, Morgan Moulder, Clyde Doyle, and James Frazier.

This implied that Party members of another very influential—if not so well publicized—group, the teaching profession, also represented a potential threat. Nor did mathematics, seemingly the most objective and apolitical of educational topics, provide immunity for its practitioners. As the New York Times reported on February 26, 1953, a figure no less influential than Dwight Eisenhower had done more than suggest, in his second press conference as president, that even mathematics teaching and textbooks could be used to “put across a doctrine.” Yet, when Louis Weisner of Hunter College in New York City, Gerald Harrison at Wayne University in Detroit, Chandler Davis at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and Lee Lorch at Fisk University in Nashville found themselves summoned in 1954, it had essentially nothing to do with the fact that they were mathematicians but everything to do with the fact that they were suspected communists teaching at American institutions of higher education.

The American Mathematical Society in the Early Days of the Red Scare

Senior members and officers of the AMS were not unfamiliar with cases similar to those of Weisner, Harrison, Davis, and Lorch, men to whom we will refer collectively as the “group of four.” Perhaps the earliest example of the AMS taking a public stand in the anti-communist campaign was in 1948 when the Council joined in the protests of other professional organizations and approved a resolution registering its “grave concern” with the statements, insinuations, and procedures of HUAC in its investigation of Edward Condon, nuclear physicist and Director of the Bureau of Standards Kli48, p. 629. The case against Condon was almost comically weak and amounted to nothing in the end, but it served as an early warning to the scientific community that it was being watched. It was a different matter when the committee became better prepared and, for example, called another high-profile physicist, J. Robert Oppenheimer, before it in June 1949. AMS Council members may have had second thoughts about their precedent-setting Condon resolution when scientists and mathematicians avowing communist connections, or who were being informed on, came under the spotlight.

HUAC and its legislative predecessors in the 1930s focused on individuals and organizations. A new front opened in 1947, however, when, faced with growing threats from the Soviet Union, President Truman signed US Executive Order 9835, which put in place the first general loyalty program in the United States. Although it applied only to US government employees, it was soon emulated by some state governments. The California State Legislature, for example, pressured the Regents of the University of California to require faculty to sign an oath declaring, not just simple allegiance, but also non-membership and non-belief in organizations that advocated the overthrow of the government Bla09. Clearly aimed at communist affiliations, the oath, despite strong faculty opposition, was implemented in 1950. At Berkeley, a number of faculty resignations resulted as did the actual firing of more than thirty others who refused to sign. Among the latter were at least three members of the AMS: topologist John Kelley, analyst Hans Lewy, and differential geometer Pauline Sperry.

In September 1950, the Council once again passed a resolution, this time addressed to the California Regents condemning their actions and calling for retracting the oath requirement. On December 28, 1950, it passed a further resolution declaring that the AMS would hold no meetings at the University of California until the matter was rectified. In what must have been an embarrassment for the Council, however, the general membership present at the Business Meeting the following day disapproved of such a boycott. This dissonance led to efforts over the next several years to clarify procedures, and probably led the Council to be more cautious about generating resolutions on controversial issues.Footnote2 While the AMS tried to sort itself out, the California affair was largely settled. Fired professors, who sued, won their case and were reinstated; the oath requirement was dropped by 1952.

The AMS actually formed an ad hoc committee in 1952 on “Controversial Questions” specifically to consider what, as a professional society, its boundaries were or should be in cases like the California oath controversy. For the events leading up to this committee’s formation, see Pit88, pp. 297–299 and Bar20.

A new opportunity for Council caution quickly came up, though. In April 1951, Oklahoma instituted much the same oath requirement as had California, and among the non-signers who were fired were five mathematicians at Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Oklahoma State University–Stillwater) and two at the University of Oklahoma. This time in response a committee joint with the Mathematical Association of America was formed to determine the facts. Each organization presented similar resolutions in 1952 to both university and Oklahoma government leaders conveying, without any censure, that their actions were dangerous for individual liberty and freedom of thought. The AMS resolution, in particular, spelled out an obvious but seemingly often unacknowledged argument in connection with the purges: “It is not to be expected that such legislation will be effective in eliminating from the faculties men who are dangerous to the national welfare, so that the injury caused is a useless waste, as at Oklahoma A. & M. College, where a department of mathematics which had achieved much recognition for its mathematical work was seriously damaged” Beg52, pp. 617–618. The largest mathematical contingent targeted at Oklahoma A&M were members of a research group headed by Ainsley Diamond and Nachman Aronszajn. The chair of the joint committee, William Duren then also chair of the mathematics department at Tulane University in New Orleans, later recalled that

We were not able to do much for Ainsley Diamond, chairman at Oklahoma State University. When I got to Stillwater one of the department members took me aside confidentially and said to me: “Duren, there is something you don’t know about this. He is a homosexual. We couldn’t say that!” The word gay had not been coined then, so they used communist as a euphemism for homosexual. Diamond was gay but no communist in the real sense. He was an excellent mathematician, a good man, and apparently ran his department well. We said so, but he stayed fired. Dur96, p. 132

Diamond and Aronszajn promptly moved with their Office of Naval Research grant to the University of Kansas where they proved a welcome addition Pri70, pp. 329–330.

During this same period in the 1950s, the AMS and MAA, along with many other national organizations, were called upon to boycott cities in which racially integrated gatherings were not possible. Lee Lorch, for one, kept this issue before the two mathematical societies. Since not authorizing meetings in such places would essentially mean no meetings in the South, the AMS Council, in particular, sought compromises to avoid cutting itself off from its members there.Footnote3 One significant result, however, was finally developing procedures to help ensure that the Council avoided the California embarrassment and to represent more accurately the sense of the total membership. The outcome was the current Article IV, Section 8 of the by-laws which establishes rules under which the Council “shall have the power to speak” for the AMS on “matters affecting the status of mathematics or mathematicians” and which gives examples clearly covering the four cases considered here Pit88, p. 297.

Determining suitable meeting places is a perennial issue facing national organizations. For an account of the development of the AMS’s procedures to deal with it in the 1950s, see Pit88, pp. 297–300.

Although adopted in December 1953, in time to apply to the “group of four,” there was never unanimity. Some felt that, while all well and good, this “power to speak” should never actually be used. Two of the most senior members advising the Council on the matter, Theophil Hildebrandt, AMS president from 1945 to 1946, and G. Baley Price of the University of Kansas, expressed their misgivings. The former decried a tendency he detected to move away from the founding stricture of the AMS that it concern itself with mathematical scholarship and research. “If we keep on in this way we will be taking over the functions of the American Association of University Professors or become a Labor Union” Hil.Footnote4 For his part, Price concluded a letter of February 23, 1952 to AMS Secretary Ed Begle this way:

See Box 5, Folder: Organizations, American Mathematical Society, Committees: Loyalty Oath 1950–1951, Minority Report, p. 1.

I agree with Professor Hildebrandt that the Society should not be concerned with the conditions of employment, salary, promotion, or teaching loads of individuals. I should not like to see the Society develop in the direction of a labor union nor take over activities which belong to the American Association of University Professors. If the conditions of employment of mathematicians throughout the nation, or of a large part of it, were to become such that the nation was weakened mathematically, it might be entirely necessary and proper for the Society to take action. This position appears to me to justify the steps which the Council took concerning the difficulties at Berkeley. PriFootnote5

For those agreeing with this position, the questions of how many individuals would constitute a “large part” and of how to assess relative mathematical strength might still arise. Nevertheless, four mathematicians at four institutions—hardly a “large part”—would have been disqualified for special attention had these standards been adhered to.

The “Group of Four” in 1954

Louis Weisner (Figure 2) was the first of the four to find himself facing inquisitors, in his case the Special Committee of the Board of Higher Education of the City of New York. Frank Nelson Cole’s last PhD student at Columbia, Weisner wrote his 1923 dissertation on “Groups Whose Maximal Cyclic Subgroups are Independent.” After an instructorship at the University of Rochester from 1923 to 1926 and a year at Harvard on a National Research Council fellowship, he landed an instructorship at Hunter College in 1927. By 1936, he had moved up through the ranks to become an associate professor with tenure. He joined the Communist Party two years later.

The Mathematics Department of Hunter College in 1936. Louis Weisner (1899–1989) is the first person on the left in the front row. (Mina Rees (see below) is the second person on the right in the first row.) Photo from The Wistarion (1936), p. 207.

As early as 1939, the New York State Legislature had enacted a Civil Service Law that stipulated that “no person shall be appointed to or retained in the public service nor in any public educational institution who becomes a member of any organization which advocates the overthrow of government by force or violence, or by any unlawful means” Gui.Footnote6 Although on the books, it was not actively enforced until after, first, the passage of the infamous FeinbergFootnote7 Law in March 1949, which required all employees not only to attest that they were not members of the Communist Party but also to inform the president of the State University of New York if they ever had been, and, second, the formation in July 1953 of a Special Committee of the Board of Higher Education. The latter was tasked specifically to “undertake an investigative program designed to obtain all of the facts and available information relating to the membership and activities of any college staff members in or connected with subversive organizations and particularly of the Communist Party, and to take or recommend such actions as the facts warrant.” When two of Weisner’s colleagues, V. Jerauld McGill in the Department of Psychology and Philosophy and Charles W. Hughes in the Music Department, were summoned before the Special Committee, Weisner voluntarily stepped forward on their behalf. Admitting that he, too, had been a member of the Communist Party, he explained that the meetings that he, McGill, and Hughes had attended merely involved, in Lee Lorch’s words, discussions of “general political questions, current events and trade union matters” and “that never had anything illegal ever been done or advocated, nor had force and violence ever been proposed” Lor88, p. 1118. Instead of assuaging the committee, however, Weisner’s admission prompted its members to demand that he provide the names of others who had been present at party meetings so that they, too, could be brought up on charges. Weisner’s refusal to name names in his interrogation on March 26, 1954 resulted in the verdict that, in willfully failing to disclose “all of the facts or information” at his disposal, he was guilty of “neglect of duty and conduct unbecoming a member of the staff” Min54, p. 511 (emphasis in the original). Before the Board could formally fire him, though, Weisner took early retirement, enabling him at least to tap into what, after twenty-seven years on the faculty, was a modest pension Lor88, p. 1118.

The cases of Harrison and Davis were different. Since they were both implicated in HUAC’s investigations of higher education in the State of Michigan, they were grilled by a standing committee of the US House of Representatives that not only had its own counsel and investigators but also a covert pipeline to the FBI and its files. Those who failed to answer questions to the satisfaction of this committee ran the risk of being cited for contempt of Congress and so of actual jail time.

Gerald Harrison (1916–2000) before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in Detroit, May 3, 1954.

Gerald Harrison (Figure 3) had taken a job teaching mathematics at New Mexico State College in Las Cruces in 1939 H-GH54, p. 5013.Footnote8 From 1941 to 1943, he had worked under Morgan Ward at Caltech, earning his PhD in 1943 for a thesis on “The Lattice Structure of Moduls.” Although born and raised in Canada, he had derived his American citizenship from his father and so was perfectly eligible to work in defense-related areas in the United States. The remaining war years found him employed, first, as a contract physicist at the Naval Ordnance Laboratory in Washington, DC and, then, as a researcher at the Harvard Underwater Sound Laboratory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Immediately postwar, he held positions at MIT’s Radiation Laboratory as well as at the Sperry Gyroscope Co. in Lake Success on Long Island. By the fall of 1948, he had become an assistant professor in the mathematics department at Wayne University (now Wayne State University) in Detroit, and by May 1954, HUAC had him in its sights.

The biographical information about Harrison that follows is from his testimony before HUAC H-GH54, pp. 5013–5018.

Harrison had raised red flags for HUAC for several reasons. First and foremost, other testimony the committee had heard alleged that Harrison had been a member of Communist Party sections in both Michigan and Boston. It also suspected him of involvement, after his arrival in Detroit, with the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), an organization thought by HUAC, again based on other testimonies, to be communist-infiltrated in the 1940s. When he came before HUAC in Detroit on May 3, 1954, Harrison was intensely grilled on these questions by Gordon Scherer (R-Ohio) and Kit Clardy (R-Mich.), the latter known as “Michigan’s McCarthy.”

As a lead-up to hammering the mathematician about his alleged membership in the CPUSA, the HUAC interrogators pressed for details on an array of what they viewed as questionable points in his history. For example, his war work, as well as his work at both the Rad Lab and Sperry, involved government contracts and, at times, work of a classified nature. Indeed, when Sperry discovered that Harrison did not have the appropriate clearance to be working on the projects to which he had been assigned, he was let go H-GH54, p. 5029. HUAC suspected that he had actually been fired because he had not honestly filled out a question on his clearance form about his membership in the Communist Party. Then, when asked whether he was an AFT member, Harrison, as he did in response to all such questions of membership, invoked the Constitution. “I feel,” he said, “that this is an invasion of my rights under the first amendment which prohibits Congress from legislating and therefore dealing in such questions relating to my right of assembly and free speech” H-GH54, p. 5022. Clardy immediately countered, directing Harrison to answer and laying down unequivocally what he and his HUAC colleagues viewed as the ground rules:

[W]e do recognize the right of counsel to advise the witness to invoke the fifth amendment properly so long as it is not done capriciously and, as you know, without any danger of possible recrimination. We do not—and I say this so that everyone may understand it—at any time recognize the right of any witness to refuse to answer on any other ground so far as the Constitution is concerned. …[S]ince this is the first witness and there are others here, I might as well make it plain that the invocation of those other amendments has been attempted many times, has been rejected, and will not be accepted by the subcommittee as a reason. H-GH54, pp. 5022–5023 (our emphasis)

Harrison nevertheless continued to invoke the First Amendment , as had the Hollywood Ten in their trials in 1948 and 1950. Somewhat later in his testimony, however, Harrison also invoked the Fifth and Sixth Amendments H-GH54, p. 5024, as Clardy and Scherer ruthlessly pressed him to answer their question about whether or not he had been a member of the CPUSA. As a result of his testimony, Harrison was first suspended and then dismissed by the administration of Wayne University.

Chandler Davis (1926–2022) with his letter of dismissal from University of Michigan President Harlan Hatcher, the lead story in the Michigan Daily, August 3, 1954.

On May 10, 1954, just a week after Harrison’s ordeal before HUAC in Detroit, Chandler Davis (Figure 4)—together with his University of Michigan colleagues, Nathaniel Coburn in mathematics, Mark Nickerson in pharmacology, and Clement Markert in zoology—was called to face Clardy and his colleagues in nearby Lansing.Footnote9 Coburn, the author of a popular vector and tensor analysis textbook, was excused from appearing due to illness (multiple sclerosis) and no further action was ultimately taken against him Dav88, p. 420. Davis, who had joined the Communist Party for the first time when he was in his teens, had quit it prior to enlisting in the Navy during World War II but had rejoined in 1946 when he started graduate school at Harvard.Footnote10 Four years later, with the PhD in hand on “Lattices and Modal Operators” that he had done under the direction of Garrett Birkhoff, Davis passed up a job at UCLA, owing to the oath controversy then raging in California, and instead accepted an instructorship at Michigan. While in Ann Arbor, he continued his various Communist Party activities and received the first sign of the government’s interest in him when officials from the State Department showed up at his apartment in 1952 and demanded that he and his wife relinquish their passports. It came as no real surprise, then, when an actual summons by HUAC followed in 1954 Dav88, pp. 419–420.

The recent work Bat23 provides much detail on Davis’s encounter with HUAC, his ensuing troubles at Michigan, and his later legal battles.

Davis had been an undergraduate at Harvard from 1942 to 1945 and had earned his BS there prior to his naval tour of duty.

The tenor and content of Davis’s testimony was not unlike Harrison’s. The committee relentlessly pressed him about his membership and participation in the Communist Party, in his case, though, the specific issue was the authorship of a pamphlet, strongly critical of HUAC, that was published and distributed under the auspices of the Council of Arts, Sciences, and Professions, a group in Ann Arbor comprised primarily of faculty and graduate students. Davis, though, steadfastly invoked the First Amendment—without subsequently adding other amendments as Harrison had—as he consistently refused to answer each question that he deemed political in nature. He also refused to name names. The committee’s frustration is quite apparent in the following exchange:

Dr. Davis. This is a question?

Mr. Clardy. I am telling you the facts, sir. Isn’t the reason that you are refusing to answer this question or say anything about it because of its Communist origin, inspiration, and direction?

Dr. Davis. Is this a question also?

Mr. Clardy. Yes, sir. If you don’t understand questions, then that line of degrees that you have has misled me terribly. Now, can you answer it?

…

Dr. Davis. The answer to that question is the same as the answers I have given previously to questions about my political beliefs or affiliations. H-CD54, pp. 5360–5361

The exchange concluded:

Mr. Scherer. This witness is clearly in contempt of the Congress of the United States.

Mr. Clardy. There is no doubt about that. He has been in contempt all day here …. H-CD54, p. 5361

Indeed, as far as the committee was concerned, it was only the invocation of the Fifth Amendment, against self-incrimination, that would forestall a contempt of Congress citation for failure to answer, as Clardy made resoundingly clear in his response to Harrison and which may have led Harrison eventually to invoke it.

The student-run Michigan Daily reported the next day on petitions being circulated by students and faculty on behalf of Davis, Nickerson, and Markert Wil.Footnote11 The topologist Edwin Moise already had twenty-seven of his fellow mathematics faculty members’ signatures in support of Davis by press time.Footnote12 The university administration also went into action by immediately suspending the three men pending the findings of an internal investigation by a Special Advisory Committee to Michigan President, Harlan Hatcher. On May 12, the Michigan Daily’s headline read “Clardy Praises Hatcher For Cooperation of ‘U’.” It also ran a front-page news item on the parallel happenings at Hunter College with Louis Weisner and his colleagues, quoting the Hunter College undergraduate newspaper:

Folder 86-036/41: Faculty Dismissals, Chan Davis, etc. 1954. The news clippings from the Daily Michigan referred to here and below may also be found in this folder.

We have not found a copy of Moise’s petition, but it would be interesting to know if Hildebrandt, the department chair, signed, given his opinion, quoted above, of how the AMS should respond in such a situation.

If these men were preaching Communistic ideology to their students, then they are a danger to our community.

But if they remained true to the ethics of their profession, then their suspension, while legal, is contradictory to the basic ethics of democracy.

Hatcher’s announcement of the formation of his Special Advisory Committee at a meeting of the University Senate on May 17 not only prompted spirited debate within and outside the university but also served to call the president’s judgment into question. As the minutes of that meeting recorded, Hatcher argued that “[t]he recent refusal of three faculty members to answer questions before the House Subcommittee on Un-American Activities … creates a problem because the questions are ones which need to be answered and because the refusal places on each person the obligation to explain his actions to his colleagues and institution” Wil.Footnote13 It was, however, not just this assumption that drew the fire of members of the faculty and student body as well as of the student paper. Tensions had also been heightened between the Faculty Senate and President Hatcher due to a motion put forward by Raymond Wilder, Michigan topologist and President Elect of the AMS, that called for an investigation of the administration’s actions with respect to the implicated professors. The “ ‘U’ family,” at least as the associate editorial director of the Michigan Daily saw it on May 21, had become “estranged.” Wilder, along with Moise, would soon also become a key player in the mathematical community’s response to Red-hunting on a national level (see below). The situation at Michigan gave him first-hand experience of how the search for Reds could disrupt academia Sch86.

The estrangement only deepened in the months that followed. As far as Davis’s case went, an interview before the Special Advisory Committee at the end of May was followed first by a lengthy and detailed statement written by Davis in mid-June and then by Hatcher’s ruling in July: Davis would be fired because of his refusal to answer various questions put to him by HUAC as well as by the president and his Special Committee. The Board of Regents officially dismissed both Davis and Nickerson on August 26; it reinstated Markert, who was judged cooperative in answering questions and no longer an adherent of communism. In August, Davis was also indicted for contempt of Congress. As Davis later put it, he next “hung around Ann Arbor, jobless and under indictment, trying to make new plans” Dav88, p. 424. The local political fallout for President Hatcher continued to make news well into the fall.

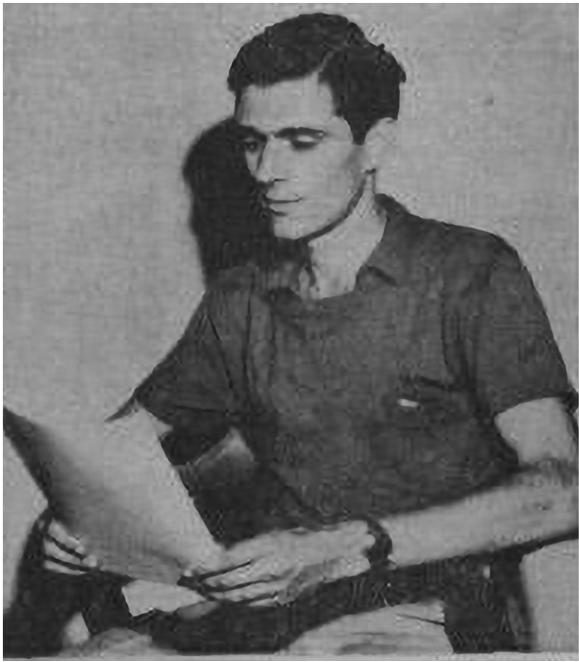

Perhaps the most visible of the four mathematicians who found themselves in seriously hot political water in 1954, however, was Lee Lorch, chair of the Department of Mathematics at Fisk University. Lorch (Figure 5), who had earned his PhD under Otto Szász at the University of Cincinnati in 1941 for a thesis on “Some Problems on the Borel Summability of Fourier Series” before enlisting in the Army during World War II, had been pushing against the system since at least 1949. As an instructor at City College of New York (CCNY), he was not reappointed in his fourth year, a reappointment that would have effectively meant tenure. The New York Herald Tribune on June 9, 1949, described both the appeal Lorch made to the Board of Higher Education and a city councilman’s opinion on the reasons behind the decision. According to the latter, Lorch was let go because of “his religion [he was Jewish] and because he had been active as vice-chairman of the Committee to End Discrimination in Stuyvesant Town, where he lives” Lor.Footnote14 The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, owner and developer of the Lower East Side community of Stuyvesant Town, used the Jim Crow laws of the day to keep Blacks out, and the issue had galvanized the desegregation activities of Lorch and others.

Lee Lorch (1915–2014), left, after losing his City College position, being interviewed by James Booker for the New York Amsterdam News, June 24, 1950.

His appeal unsuccessful, Lorch managed to obtain a position at Pennsylvania State University in State College but was let go from that job after just one year. In a widely reported stand, Lorch and his wife, Grace, had invited an African-American family to live rent-free in their Stuyvesant Town apartment while they were in State College, and although the Penn State administration, like that of CCNY, officially justified its action on the basis of Lorch’s “personal qualifications,” an assistant to the Penn State president was reported to have said that Lorch’s actions relative to the African-American family in New York City were “illegal, immoral, and damaging to the public relations of the College” Wil.Footnote15 Again, Lorch appealed to no avail, in spite of enlisting the support of no less a figure than Albert Einstein. These difficulties gradually brought Lorch’s case within the ambit of the American Mathematical Society.

Folder 86-036/31: Lorch case, 1950–1957, Julian Blau et al. to the Faculty of Pennsylvania State College, undated (but spring of 1950).

John Kline, AMS Secretary, topologist at the University of Pennsylvania, and clearinghouse of information mathematical, had first heard of Lorch’s troubles at CCNY in 1949 from Samuel Eilenberg and Paul Smith, both at nearby Columbia Wil.Footnote16 In April 1950, Lorch and Kline had met at the AMS meeting held in Washington, D.C., to discuss the situation at Penn State, even though Kline was in no particular position to help. A month later in May, Kline received a letter from the same Raymond Wilder at Michigan who would become involved in Chandler Davis’s troubles four years later in 1954, asking Kline what he knew about Lorch’s case.

Lorch’s next move, in 1950 and with its administration’s full knowledge of his prior difficulties, was to Fisk. Popular with both colleagues and students, Lorch settled in well there, becoming active in the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), receiving outside funding for his research, serving as department chair, and working in various ways to put the mathematics department of the historically Black institution on the mathematical map. Even the national scene began to look rosy for those with Lorch’s political and social commitments, when on May 17, 1954, the US Supreme Court delivered its unanimous ruling in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, to the effect that the segregation of public schools was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and therefore unconstitutional. The Lorches immediately sought to test this new principle by requesting of the Nashville School Board that their daughter, Alice, be “admit[ted] to the only public school in [their] neighborhood,” namely, a segregated school for Blacks only Wil.Footnote17

Folder 86-036/31: Lorch case 1950–1957, Lorch to the Fisk Board of Trustees, October 28, 1954. Lorch’s Mathematics Department colleague, Robert Rempfer, and his wife, Gertrude, a physics professor at Fisk, also tried (unsuccessfully) to have their children enrolled at the same Black school.

Almost immediately thereafter, on September 7, Lorch was served with a subpoena by HUAC, commanding that he face that tribunal—comprised in his case of Clardy, Scherer, and Francis Walker (R-Penn.), together with Frank Tavenner as HUAC’s counsel—just one week later and some 350 miles away in Dayton, Ohio. Due to the extremely short notice, Lorch was forced to present himself without the benefit of counsel H-LL54, p. 6953. Clardy, however, made the committee’s position clear and set the adversarial tone of the proceedings from the outset. “A week, better than a week’s time is ample for anybody, and I should suggest this to you, Mr. Witness, that if the matter should be put over from today you might be put to the trouble and inconvenience at your own expense of coming to Washington. Now that is a matter you should give some consideration to” H-LL54, p. 6955. (The rules of the committee allowed witnesses to apply for “travel allowances and attendance fees,” but gave no guarantee USC53, p. 9.)

In the context of its standard questioning regarding educational and employment history, the Committee focused, as it had done in Harrison’s case, on Lorch’s involvement, while a student at the University of Cincinnati in the early 1940s, with the AFT H-LL54, p. 6959. The FBI, usually willing to share its own investigations with HUAC, maintained a file on Lorch that indicates he was a subject of interest from October 1941 to February 1973.Footnote18 At issue was Lorch’s alleged—by husband-and-wife FBI informants in 1950Footnote19—attendance in July 1941 at the American Youth Congress in Philadelphia as an AFT member. Tavenner asked him point-blank: “Were you a member of the Communist Party at the time you attended the American Youth Congress … at Philadelphia?” H-LL54, p. 6960. When delaying maneuvers worked for only so long, Lorch also opted to invoke the First Amendment “on the grounds that a committee planning, investigating for the purpose of securing legislation cannot take the standpoint that it is [holding] an investigation which can lead to a violation of any of the rights protected by this first amendment” H-LL54, pp. 6962–6963.Footnote20 But Lorch did even more. In the context of registering once again his objections to not having counsel present, he stated that “[f]or me to know what to prepare for was actually a very difficult thing. I am [Tennessee]-State vice president of the NAACP. As such, I might be presumed to be interested in bringing before this committee any information which might be valuable concerning efforts being made to subvert the Constitution of the United States in accordance with [the] decision of May 17 as to antisegregation in education” H-LL54, p. 6963. Clardy shot back: “You know you are going deliberately far afield. Come back to the beam.”

Lorch only saw the record of the 1950 hearing in which he was named for the first time on October 9, 1954, three weeks after he had testified before HUAC.

A lightly annotated copy of Lorch’s testimony before HUAC may be found in Lor, 207-054/025(27). The words in square brackets here and below are his penciled emendations of the transcript.

More questioning, about Lorch’s alleged—by the same FBI informants—attendance at a meeting of the CPUSA in Cincinnati in July 1941 resulted in Lorch’s invocation yet again of the First Amendment and, this time, in Scherer’s unequivocal conclusion: “Witness, I am advising you that you are clearly in contempt, legal contempt of the Congress now under the two answers that you have given. There is no question about it” H-LL54, p. 6965. It was only when, in the closing minutes of his testimony, Tavenner asked Lorch if he was “a member of the Communist Party when [he] accepted [his] position at Fisk University in 1950” H-LL54, p. 6976 that Lorch relented somewhat in his hardline approach to the committee. “Again, for the purposes of safeguarding my institution, against the barrage of newspaper publicity which might accompany this, and which is intended to, by virtue of the public nature of these hearings, I answer that question, too, in the negative, but again with a protest that the committee has no right to pose such a question because of constitutional safeguards and because of its own rules” H-LL54, p. 6977. Despite this effort to spare Fisk University, Lorch was called before Fisk’s Board of Trustees at the end of October 1954 and told in December that his contract would not be extended beyond the end of June 1955. Also in December, he was indicted for contempt of Congress. In analyzing his situation after the fact, Lorch agreed with the April 16, 1955 assessment of a writer for the Washington, D.C.-based newspaper, Afro-American, namely, that the real reason for Lorch’s troubles at Fisk owed to the “bitter-end segregationists in Nashville” and the Dixiecrats who “called upon an agency of the House of Representatives to do their dirty work” Wil.Footnote21

The AMS Committee on Displaced Persons

By the winter of 1955, the plights of Weisner, Harrison, Davis, and Lorch had come officially to the attention of the American Mathematical Society through the intervention particularly of Lorch’s friend and Davis’s colleague, Edwin Moise. In his capacity by that time as AMS President, Moise’s and Davis’s friend and colleague, Raymond Wilder, had received word of his authorization—in a letter from AMS Secretary Edward Begle dated January 12, 1955—“to appoint a committee to consider what could and should be done in order to avoid the termination of the mathematical careers of certain people who have been dismissed for political reasons” Wil.Footnote22 Begle understood this charge for the challenge that it was, however. “It will undoubtedly be very difficult to find the proper people for this one,” he told Wilder. Still, Wilder had some initial ideas that he jotted down at the bottom of Begle’s letter. His (apparently) top choices, as they were bracketed by a large parenthesis and linked by an asterisk to the relevant paragraph, were Moise, Bill Duren, Saunders Mac Lane at Chicago, R(alph) D. James of the University of British Columbia, and Cornell’s J. Barkley Rosser.

A first round of letters went out a month later. In reply, Mac Lane, who was then chair of his department, pled press of work in declining to serve, although he felt compelled to “confess in addition that my regard for the wisdom of Mr. Chandler Davis is very low, although this does not disqualify me by itself” Wil.Footnote23 Duren, a Southerner, who, as noted, had served on the AMS-MAA committee investigating the Oklahoma loyalty oath matter, was still department chair and also overworked, but, in reluctantly agreeing to serve, offered that “we can not afford to give up in our efforts for a resolution of the problem of intellectual freedom as it applies in mathematics particularly, and therefore I feel that if I am called on I should serve, even though the Committee would seem to be a rather futile one.” A pragmatist, he added that “In my part of the country, we operate as follows in a situation of the sort which you are talking about. We ignore the general principle, and avoid clashes in doctrine; but we say: ‘Joe is a friend of mine. I know he is all right. He needs a job.’ I think this might work in other parts of the country as well, but the trouble is that most of our dischargees demand satisfaction on the basis of their principles” Wil.Footnote24 James and Rosser also agreed to serve, although the former wondered if the fact that he was Canadian might be a problem for the AMS while the latter feared that his over-stretched commitments in his department would affect his ability to do committee work in a timely way.

Under Moise as chair, this would have constituted a presumably ample committee of four, but Wilder actually had broader considerations in mind. In writing to Claude Shannon at Bell Labs on March 9, he explained that he had “to date, besides the chairman (E. E. Moise) found a suitable man to represent the smaller colleges (Duren), a Canadian member of the Society (R. D. James), and am hoping to find in addition someone from the private eastern universities as well as someone from industry” Wil.Footnote25 Shannon, although “in sympathy with the idea that these mathematicians should receive a fair break,” begged off, but suggested his Bell Labs colleagues, Hendrik Bode and Brockway MacMillan Wil.Footnote26 When Wilder extended the invitation to Bode, Director of Mathematical Research, he had no better luck. Bode, however, offered the advice that, if helping to find positions in industry for displaced mathematicians was a priority, then it should be understood that a university mathematician would likely need “to spend at least a few months’ extra training in rounding out his physical background or in getting acquainted with some of the obvious applied fields, such as statistics or numerical methods” Wil.Footnote27 He also recommended asking the advice of Hunter College’s Mina Rees (Figure 2), who had recently left her position as deputy science director of the Office of Naval Research. In a letter of thanks to Bode, Wilder recounted his meeting with Rees during a visit to New York City and her recommendation of Harold Kuhn, president of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. Wilder was particularly pleased that he could easily approach Kuhn since the latter, normally at Princeton, was “spending the summer two doors down the hall from me” at the University of Michigan Wil.Footnote28

Kuhn’s acceptance over the summer finally completed the committee that Wilder had envisioned, even though Moise, Duren, James, and Rosser had already begun their work in early May. Begle had been right. It had been far from an easy committee to constitute.

That there were concerns in the mid-1950s about the general political climate and its effects on the American mathematical community was evidenced by more than the formation of this committee, however. For example, Wilder received at least two letters from Chicago’s Irving Segal urging him as AMS president to create some sort of mechanism that would allow, as he put it in February 1955, the AMS “to receive and disperse voluntary contributions for the financial support of bona fide research mathematicians who are unable to practice their profession for political reasons” Wil.Footnote29 Wilder, probably recognizing that he would not be the only one to see the highly impractical nature of this idea, diplomatically avoided disagreeing and instead made clear that he too was “very much disturbed by the effect of the current hysteria on our profession, particularly in those cases where there is a threat of virtual ostracism. That scientific and mathematical ability is in short supply at present,” he continued, “seems to be generally conceded, and the manner in which [we] are rendering some of it unusable, aside from the ethical questions involved, is a tragedy in my opinion” Wil.Footnote30 Fortunately, Wilder could pass Segal’s idea on to the committee he was forming. In May, Segal reinforced his proposal with the claim that it would be possible to come up with objective criteria for a “bona fide” candidate and for allocating appropriate amounts of money. He also offered a dubious implication of what he cited as a historical precedent, namely, “[t]hat it is legitimate for this Society to act as agent for this purpose is implied by its decision in the California loyalty oath case” Wil.Footnote31 Wilder assured Segal in reply that the matter was now before the committee along with a related proposal from Lorch to create or support some sort of “foundation … to finance projects for displaced people” Wil.Footnote32 At the same time, he made it clear, contrary to what Segal may have thought, that the AMS “did not collect money for the California professors” and that it would likely “not be feasible” for it “to undertake the handling of funds” in the present situation. As Begle put it, that “would be a great headache for the Society.” For his part, Wilder “much prefer[red] to have any such operation carried out by an independent group.”

Folder 86-036/31: Lorch case, 1950–1957, Wilder to Segal, May 26, 1955. The quotations that follow in this paragraph are also from this letter.

Still, another financial suggestion, from two of Lorch’s friends in California, computational number-theorist D. H. “Dick” Lehmer at Berkeley and complex analyst and mathematical physicist Max Schiffer at Stanford, prompted further discussion of such matters. In August 1955, they urged the AMS to “look into the matter of financial aid for legal expenses in order to aid mathematicians who are under political fire, in order that they be not deprived of their legal rights for want of a few thousand dollars” Wil.Footnote33 This became an even more pressing issue for Lorch, in particular, after his December indictment.

That Wilder rendered an opinion to Segal after consulting with Begle but before hearing from the committee may have been because he detected signs of inaction. Unfortunately, under Moise, and despite his initiation of it, the committee proved somewhat rudderless throughout the fall of 1955. Writing to Kuhn on January 24, 1956, Wilder offered that Moise was “apparently a rather poor letter writer” and actually “feels that the crisis no longer exists, since the people involved have generally got other positions” Wil.Footnote34 Nevertheless, Wilder thought “that there are recommendations the committee might make that would be of value should crises again arise,” and one of those specifically concerned the as-yet unresolved matter of financial support for legal fees.

In March 1956, Moise, spurred into action by a direct appeal from Lorch, and admitting to his “sheer negligence,” finally raised the issue explicitly with his committee and asked for their opinions on it at the same time that he shared his own Wil.Footnote35 He was opposed to asking the AMS to collect funds for Lorch, but he was quick to add that he did “not feel happy about this conclusion. The known facts about Lorch and the plausible conjectures which may be based on them do not, in my opinion, justify his being sent to jail; and I think that the hearings on which the contempt citation was based represented very bad public policy. Thus my conclusions on the matter in hand reflect not so much a view of the Lorch case as a view of the Society’s proper role in such matters.”

Folder 86-036/31: Lorch case 1950–1957, Moise to Duren, James, Kuhn, and Rosser, March 22, 1956 (the quotation that follows is also from this letter).

The AMS Council apparently agreed, for when Berkeley’s David Blackwell, a Council member, proposed that such a committee be set up, his recommendation was not adopted Wil.Footnote36 Instead, the Council suggested that “if a private committee were set up, an announcement of the committee could appear in the News and Notices of the Society,” that is, the “News Items and Announcements” section of the Notices of the AMS, a journal that had been created in 1954 in part for the purpose of carrying informal communications of professional interest. Blackwell set to work and soon had such a committee in place. Indicative of the precedent-setting nature of this move and of the AMS’s evolving position of maintaining a certain distance from the issue, however, both Wilder as AMS president and Richard Brauer as AMS president-elect declined Blackwell’s invitation to serve on his committee. Wilder put it this way: “There’s no question how I personally feel about these indictments. … I am bothered, however, by the fact that I am still president of the Society, and that the Society decided not to take official action. … I know I could participate as an individual mathematician, but to many it would look otherwise and I believe I’d better say no” Wil.Footnote37 He was more candid in a letter to Brauer. “I’ll admit,” he said, “that I have got personally somewhat tired of writing innumerable letters for people who seem to get into difficulties repeatedly. I have done so in Lorch’s case, and am convinced, between you and me, that he isn’t happy unless he’s under indictment or something comparable” Wil.Footnote38 Wilder’s exasperation was understandable given that he had been flooded with documents and requests from Lorch since early 1955. He did contribute money to Lorch’s legal defense fund, however, if not his name to the actual committee, and he continued to respond positively to requests from Lorch in support of various causes for at least the next two decades Wil.Footnote39

Folder 86-036/7: Le-Ly, Blackwell to Wilder, September 4, 1956 (the quotation that follows is from this letter).

When an announcement of Blackwell’s committee appeared in the Notices in November 1956, it listed not only the members—Blackwell, Lehmer, Ralph Phillips, John Roberts, Gabor Szegö, and Antoni Zygmund—but also sounded the call for financial donations to Lorch’s legal defense fund. Unwilling to establish a central funding agency, the AMS had instead provided a communication channel for members. The decision on legal expenses having been made at the level of the Council, a recommendation from Moise’s committee was largely moot, and the AMS went no further. It therefore managed to avoid taking on anything like the trade union functions that Hildebrandt and Begle had warned against.

And Then …

The year 1954 had unquestionably been a trying one for Weisner, Harrison, Davis, and Lorch. Their professional fates were by no means clear following their respective entanglements with Red-hunting committees. Moreover, their notoriety as “displaced persons” within the American mathematical research community unexpectedly threw them together into an exclusive “club,” a band of brothers, to which others hoped never to belong. Davis learned of Lorch’s troubles and got in touch with him to offer moral support and advice Lor;Footnote40 Davis, as a fellow Michiganer, was well aware of Harrison’s plight; Lorch and Davis came to know of Weisner’s situation. Of the four, Weisner and Harrison may not have abandoned their political beliefs but continued to keep lower profiles than the more militant Davis and Lorch who regularly kept in touch with one another after 1954.

After living off his pension for a year-and-a-half, Weisner, thanks to Lorch’s active intervention, accepted a full professorship at the University of New Brunswick in Canada that Lorch had turned down in favor of an offer from Philander Smith College, a historically Black college in Little Rock, Arkansas. Weisner happily remained in Fredericton for the rest of his career, continuing his group-theoretic and combinatorial research and earning a reputation as an outstanding teacher. He was made professor emeritus in 1970.

Harrison’s career took a different turn. Unable to find a new job in academe, by 1956, he had taken a position as a systems analyst at the Teleregister Company in Stamford, CT. Teleregister, a pioneer in high-speed data transmission and display, engineered such devices as the electronic ticker tape as well as electronic reservations systems for airlines and railroads. From his new industrial post, Harrison published at least one paper on “Stationary Single-Server Queuing Processes with a Finite Number of Sources” in the journal, Operations Research, in 1959.

Both Davis and Lorch, like Weisner, ultimately returned to academe. From 1954 to 1962, Davis managed to cobble together a series of short-term positions: in industry, as a part-time teacher, on a fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study, in the employ of the AMS as an associate editor of the Mathematical Reviews. During this same period, he unsuccessfully appealed his contempt of Congress charges all the way to the Supreme Court (which refused to hear the case) and spent six months in federal prison in Danbury, CT in 1960 Dav88, p. 423. The precedent that had been set in Lorch’s case, moreover, namely, of the formation of a private committee of mathematicians for the solicitation of funds to help defray legal costs, also worked in Davis’s favor in the capable hands of William Pierce of Syracuse University Lor.Footnote41 By 1962, Davis, owing especially to the efforts of geometer Donald Coxeter, had taken the professorship at the University of Toronto that he would hold until his retirement in 1992. He continued actively to pursue not only his research in operator theory in Hilbert spaces but also his political activism, speaking out about and protesting against the Vietnam War and working for human rights.

As for Lorch, he stayed at Philander Smith College from 1955 to 1958. While there, he remained active in the NAACP and weathered, first, the dropping (by the government) of his contempt of Congress charge (in April 1956), then, the issuing of a second contempt of Congress indictment (in July 1956) on essentially the same grounds as the first, and, finally, a trial (April 1957) and acquittal (November 1957) on that second charge. He, but especially his wife, Grace, also became embroiled in the tensions surrounding the integration of Central High School in Little Rock in the fall of 1957 and found themselves, but again especially Grace, the target of the Dixiecrats Lor.Footnote42 As pressure mounted for the president of Philander Smith to dismiss Lorch and after an attempt was made in February 1958 to dynamite the Lorches’ garage, the family made the decision to leave Little Rock.Footnote43 Although Lorch blanketed North America with applications, he found himself essentially blacklisted and was initially successful in securing only a one-year visiting position at Wesleyan College. In 1959, however, an application he had made the year before to the University of Alberta bore fruit. He and his family remained in Edmonton until 1968, when Lorch accepted the professorship at York University in Toronto that he held until his retirement in 1985. Like Davis, Lorch remained active in his mathematical research, in his case in Fourier analysis, as well as in civil rights and other political and social causes.

Political Lessons

The 1950s presented unforeseen challenges of a political nature for the AMS. Loyalty oaths in the states of California and Oklahoma affected some of its members. The machinations of HUAC and its clones affected others, notably, in our example, the members of the “group of four” who lost their jobs in 1954. Relatively speaking, though, the total number of mathematicians affected was not large, while it has been estimated that from 1947 to 1956 there were 2,700 dismissals and 12,000 resignations as a result of loyalty screening among federal workers alone Sto13, p. 2. There appear, however, to be no reliable estimates for the corresponding campaigns conducted by state and local governments and their associated educational institutions, campaigns like those that ensnared Ainsley Diamond in Oklahoma and Louis Weisner in New York. Another number hard to gauge stems from the parallel but less publicized campaigns that took place based on more personal circumstances of risks to security and morality such as alcoholism, homosexuality, and having a communist relative Sto13, p. 101. Though documentation is sparse, it is known that in addition to losing jobs, some who had their careers ended took their own lives Sto13, pp. 193–194.

Given this general atmosphere of suspicion, accusation, and retribution, being called before a body like HUAC was undoubtedly a traumatic experience. Although it was probably of little immediate comfort, contemporaneous countervailing forces in the media and in government nevertheless aimed at putting an end to the anti-communist campaign, especially in its “witch-hunt” mode, on the grounds that it risked being more subversive to American democracy than the CPUSA. Even staunch anti-communists were concerned that pushed too far the campaign could become self-defeating. In 1954, as the bombastic Senator McCarthy, used to attracting media attention, was losing supporters, HUAC and its offspring still carried on, but with less of a public show. Reflective of the cautious optimism that times might be changing, Chandler Davis suggested to Lee Lorch during the fall election season in 1954 that “[t]hough it is unlikely the present Congress will convene again, therefore unlikely you will be cited for contempt, it is possible” Lor.Footnote44 Davis’s optimism proved premature, however. Congress did change hands from a Republican to a Democratic majority, but the new chair of HUAC, Francis E. Walter (D-Penn.), was at least as avid an anti-communist as his predecessors. Lorch, as noted, was cited; Davis ultimately went to jail.

Anti-communist sentiment was far from dying out, but other motivations for the continuing momentum of HUAC were evidently also at play. The case of Ainsley Diamond exemplified the fact that “communist” was used by some investigators as a cover for “homosexual,” thereby enabling two purges to be conducted under one banner.Footnote45 Racist motives seemed likely to have been behind the persistence of the cases against the Lorches and others in the South. As Grace Lorch described it, committees like HUAC aided the racist cause in at least two ways:

The first substantial historical account of the government investigations of homosexuals is provided in Joh04.

There is direct intervention in which these committees use the power of the federal Congress against individuals and organizations opposed to segregation. Recently the Washington Post observed that “The Senate Internal Security Subcommittee has long made it plain that it regards support of the equal protection clause of the United States Constitution as subversive.” (Editorial, October 30 [1957]).

Then there is the indirect help these committees supply by their example, their techniques and the atmosphere they have helped create. LorFootnote46

46✖Folder 2007-054/021(08): Remarks by Mrs. Grace Lorch, Guest of Honor, Bill of Rights Dinner of the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee, Hotel New Yorker, New York, December 17, 1957, p. 4. The Senate Internal Security Subcommittee was the Senate version of HUAC.

HUAC survived long enough to investigate protest movements of the 1960s but began to change its image with a renaming in 1969 to the Internal Security Committee. It was finally terminated in 1975.

Interestingly, the challenges that the political reality of the late 1940s and 1950s presented to the mathematical community were reflected in a series of institutional changes within the AMS. It hired its first executive director in November 1949; it moved its headquarters to Providence in 1951; it began to rely less on volunteers Pit88, pp. 251, 318, and 120–121. It created its Notices, which quickly became a medium for member news and feedback on a variety of topics. It added Article IV, Section 8 to its by-laws, thereby providing a means for its Council to speak on its behalf on non-scientific matters. The era of the Red Scare dramatically brought out for the AMS the challenge of trying to adhere to its members’ core, common interest in mathematics when political and social influences could force certain members out of the profession. The AMS’s response to the predicament of the “group of four” in 1954—as well as to that of the Californians and Oklahomans earlier in the decade—made plain the differences of opinion that can exist within a professional organization and the difficulties that it can confront in trying to deal with issues not directly related to its charter mission. Still, by putting in place a venue for member discussion and a procedure for voicing the position of the Society, the AMS was arguably better prepared by the end of the 1950s to engage with such challenges in the future.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the help of: the archival staff at York University; Carol Mead and the staff at the Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin; Matty Watson at the Archives of the University of New Brunswick; Sydney Van Nort and Jackie Rees at the Archives of the City College of New York; and the archival staff at Hunter College Library, Hunter College of the City University of New York.

References

- [Bar20]

- Michael J. Barany, “All of these political questions”: anticommunism, racism, and the origin of the Notices of the American Mathematical Society, J. Humanist. Math. 10 (2020), no. 2, 527–538, DOI 10.5642/jhummath.202002.24. MR4133974,

Show rawAMSref

\bib{Bar20}{article}{ label={Bar20}, author={Barany, Michael J.}, title={``All of these political questions'': anticommunism, racism, and the origin of the \textup {Notices of the American Mathematical Society}}, journal={J. Humanist. Math.}, volume={10}, date={2020}, number={2}, pages={527--538}, review={\MR {4133974}}, doi={10.5642/jhummath.202002.24}, } - [Bat23]

- Steve Batterson, The prosecution of Chandler Davis: McCarthyism, communism, and the myth of academic freedom, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2023.

- [Bla09]

- Bob Blauner, Resisting McCarthyism: to sign or not to sign California’s loyalty oath, Stanford: University of Stanford Press, 2009.

- [Beg52]

- E. G. Begle, The Summer meeting in East Lansing, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 58 (1952), no. 6, 612–669, DOI 10.1090/S0002-9904-1952-09650-6. MR1565432,

Show rawAMSref

\bib{Beg52}{article}{ label={Beg52}, author={Begle, E. G.}, title={The Summer meeting in East Lansing}, journal={Bull. Amer. Math. Soc.}, volume={58}, date={1952}, number={6}, pages={612--669}, issn={0002-9904}, review={\MR {1565432}}, doi={10.1090/S0002-9904-1952-09650-6}, } - [Dav88]

- Chandler Davis, The purge, A century of mathematics in America, Part I, Hist. Math., vol. 1, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, 1988, pp. 413–428. MR1003186,

Show rawAMSref

\bib{Dav88}{article}{ label={Dav88}, author={Davis, Chandler}, title={The purge}, conference={ title={A century of mathematics in America, Part I}, }, book={ series={Hist. Math.}, volume={1}, publisher={Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI}, }, date={1988}, pages={413--428}, review={\MR {1003186}}, } - [Dur96]

- William Duren, Memoirs of a lay mathematician. In Bettye Anne Case, Richard A. Askey, Paul T. Bateman, W. Wistar Comfort, and Everett Pitcher (eds.), A century of mathematical meetings, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 1996, pp. 121–168. MR3889950

- [Gui]

- Guide to the Board of Higher Education of the City of New York, Academic Freedom Case Files TAM 332: http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/tamwag/tam_332/tam_332.html.

- [Hil]

- Theophil Henry Hildebrandt Papers 1887–1978, 1930–1960, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

- [H-CD54]

- Testimony of Horace Chandler Davis, Investigation of communist activities in the State of Michigan-Part 6 (Lansing), Hearings before the Committee of Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-Third Congress, Second Session, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1954, pp. 5349–5371.

- [H-GH54]

- Testimony of Gerald I. Harrison, accompanied by his counsel, G. Leslie Field, Investigation of communist activities in the State of Michigan-Part I (Detroit-Education), Hearings before the Committee of Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-Third Congress, Second Session (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1954), pp. 5011–5036.

- [H-LL54]

- Testimony of Lee Lorch, Investigation of communist activities in the Dayton, Ohio Area-Part 3, Hearing before the Committee of Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-Third Congress, Second Session, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1954, pp. 6953–6977.

- [Joh04]

- David K. Johnson, The lavender scare: the Cold War persecution of gays and lesbians in the federal government, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- [Kli48]

- J. R. Kline, The April meeting in New York, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 54 (1948), no. 7, 622–647, DOI 10.1090/S0002-9904-1948-09030-9. MR1565071,

Show rawAMSref

\bib{Kli48}{article}{ label={Kli48}, author={Kline, J. R.}, title={The April meeting in New York}, journal={Bull. Amer. Math. Soc.}, volume={54}, date={1948}, number={7}, pages={622--647}, issn={0002-9904}, review={\MR {1565071}}, doi={10.1090/S0002-9904-1948-09030-9}, } - [Lor88]

- Lee Lorch, Letter to the editor: Louis Weisner remembered, Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 35 (1988), 1117–1118.

- [Lor]

- Fo524 Lee Lorch Fonds, York University Archives and Special Collections.

- [McC50]

- Joseph McCarthy, “Enemies from within” speech delivered in Wheeling, West Virginia (1950): 195020mccarthy20enemies.pdf (utexas.edu)

- [Min54]

- Minutes of the meeting of the Board of Higher Education of the City of New York held September 30, 1954: Board Meeting Minutes September 30, 1968 (cuny.edu)

- [New17]

- Anthony Newkirk, “The long reach of history”: the Lorches and Little Rock, 1955–1959, The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 76 (Autumn 2017), pp. 248–267.

- [Pit88]

- Everett Pitcher, American Mathematical Society centennial publications. Vol. I: A history of the second fifty years, American Mathematical Society, 1939–1988, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 1988, DOI 10.1007/bf01017168. MR1002190,

Show rawAMSref

\bib{Pit88}{book}{ label={Pit88}, author={Pitcher, Everett}, title={American Mathematical Society centennial publications. Vol. I}, subtitle={A history of the second fifty years, American Mathematical Society, 1939--1988}, publisher={American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI}, date={1988}, pages={viii+346}, isbn={0-8218-0125-2}, review={\MR {1002190}}, doi={10.1007/bf01017168}, } - [Pri70]

- G. Baley Price, History of the department of mathematics of the University of Kansas: 1866–1970, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Lawrence, KS, 1976. MR764397,

Show rawAMSref

\bib{Pri70}{book}{ label={Pri70}, author={Price, G. Baley}, title={History of the department of mathematics of the University of Kansas: 1866--1970}, publisher={University of Kansas, Lawrence, Lawrence, KS}, date={1976}, pages={xii+788}, review={\MR {764397}}, } - [Pri]

- Griffith Baley Price Papers, Archives of American Mathematics, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

- [Sch86]

- Ellen Schrecker, No ivory tower: McCarthyism and the universities, New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- [Sto13]

- Landon R. Y. Storrs, The second red scare and the unmaking of the New Deal left, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

- [USC53]

- United States, Congress. House. Committee on Un-American Activities. Rules of Procedure. Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1953.

- [Wil]

- Raymond L. Wilder Papers, 1914–1982, Archives of American Mathematics, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Credits

Figure 1 is courtesy of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection, Los Angeles Public Library.

Figure 2 is courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Hunter College Libraries, Hunter College of the City University of New York, New York City.

Figure 3 is courtesy of United Press Photo.

Figure 4 is courtesy of the Michigan Daily.

Figure 5 is used with permission of New York Amsterdam News; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Photo of Albert C. Lewis is courtesy of Albert C. Lewis.

Photo of Karen Hunger Parshall is courtesy of Bryan Parsons.