PDFLINK |

Escape from the Ivory Tower

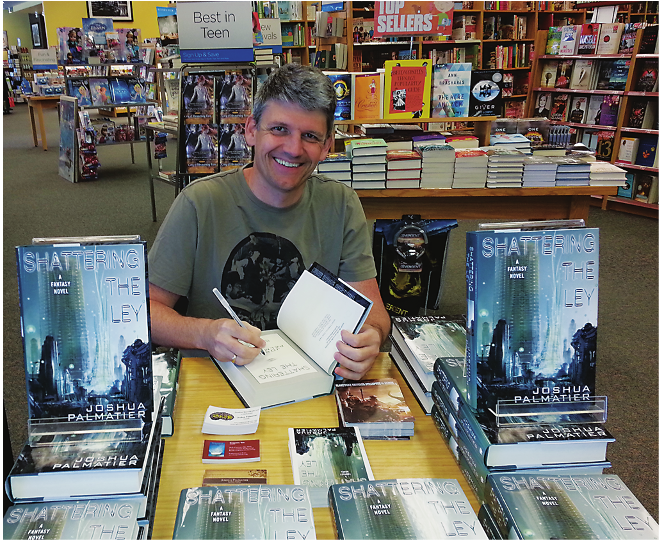

Joshua Palmatier signs copies of Shattering the Ley, the first book in his third fantasy trilogy.

In the early aughts, then PhD candidate Joshua Palmatier was expending a lot of time and mental energy trying to fathom an algebraic structure called the m-zeroid. When he tired periodically of cataloging properties or developing visualizations, got frustrated in his efforts to outline generation methods or prove equivalences, Palmatier escaped into a realm of his own creation: Amenkor, a once marvelous metropolis devastated by a mysterious force called the White Fire. There Palmatier spun the tale of Varis, a homeless orphan with a gift for perceiving people’s true natures.Footnote1

And an explicitly stated hatred for math. “Recall I wrote this book while getting my PhD,” says Palmatier, “so that explains that.”

“It was what kept me sane,” Palmatier says of the fiction he wrote while in graduate school. “Every student should have something completely different from their PhD subject to give them something to turn to when the PhD work itself becomes too stressful.”

Most of Palmatier’s professors and fellow students at SUNY Binghamton knew he was writing on the side; they mostly regarded his verbal world-building as a hobby and harmless. One professor did take Palmatier aside, though, and advise him to abandon his avocation. There was no way, he told the yet unpublished Palmatier, that he could write and get his PhD at the same time. “But that just motivated me more,” Palmatier recalls.

Juggling math and writing, see, was no idle whim for Palmatier; he had been planning the balancing act since middle school. Palmatier caught the writing bug in the eighth grade when he completed—with relish and to much acclaim—an assignment to compose a Twilight Zone-ish short story. It was fine to be a writer, his mom allowed when he came home abuzz, but he also needed a more dependable way to pay the bills. Luckily Palmatier had decided in the fifth grade, swayed by his apparent knack for explaining mathematical concepts to his peers, to teach math when he grew up.

“I decided there was no reason I couldn’t do both,” Palmatier remembers. The two pursuits would pair well, he figured, since teaching would leave him with summers free to focus on writing.

So, as Palmatier started racking up math degrees, he wrote too, honing his craft as he earned first a BS and then an MA from Penn State. The tomes he drafted during those years remain “in a trunk collecting dust,” but the product of the breathers Palmatier took from his draining contemplation of m-zeroids—The Skewed Throne, the first installment of a trilogy set in Amenkor—sold the same semester he got his PhD.

Doing math and writing epic fantasy complement each other nicely, Palmatier has found. A mathematician’s proclivity for logic and coherence comes in handy when framing fictional worlds, for one thing. “The magic has to follow a certain set of rules in order for it to make sense,” Palmatier explains. “Readers will suspend their disbelief for magic, but not if it doesn’t have its own consistency.” And the fanciful habits of mind one cultivates as an author of speculative fiction can facilitate the flashes of creative insight often required to push the boundaries of mathematical knowledge. “Being able to imagine and attempt things that aren’t ‘typical’ helped me get through my PhD,” Palmatier says. And his colleagues at SUNY Oneonta—who, Palmatier reports, tap him to “do any heavy-duty administrative write-ups for the department”—also benefit from his way with words. “Everyone knows I can probably produce something in a half hour that might take someone else an hour or two.”

Palmatier’s focus on the Oneonta campus is math (though he has overseen a few independent studies in the English department for students expressing an interest in writing fantasy novels), but in his off hours… He edits themed anthologies of fantasy and science fiction stories for his small press, Zombies Need Brains. He manages his lately launched online magazine, ZNB Presents. And he writes. Palmatier aims for 1000 words per day when classes are in session, 2500 when they’re not.

He doesn’t think the authors he deals with—members of his local writers group, say, or those submitting work for his editorial review—pay his math teaching much heed (if, indeed, they’re even aware of it). “Almost every writer has a day job,” he says. “We all understand that a day job is basically a necessity and it’s just a matter of figuring out how to work the writing into the schedule without burning yourself out.” For Palmatier, this means not letting the math side of his life take over. He sets aside a few hours a day to write, fiercely guards those daily windows against encroachment from other commitments, and leverages willpower to ensure that he sits down and actually does the creative work. “It’s really all about organizing your time and sticking to your plan,” he says.

Although math has been largely absent from Palmatier’s fiction to date, his latest series—due out later this year—realizes his long-percolating idea of using the m-zeroid (the subject of his dissertation research) as the basis for a system of magic. The protagonist of the Crystal Cities trilogy—a mathematician—discovers over the course of the story the mathematical structure—inspired by the m-zeroid—underlying the mages’ wizardry. Two tetrahedrons are joined along one face to form a triangular bipyramid.Footnote2 Nodes corresponding to particular aspects of a magical phenomenon are selected in the bottom tetrahedron to pick out a unique node in the upper tetrahedron corresponding to the specific magic to be implemented.Footnote3 Palmatier does not bog down the novels’ flow with the “gory details” of the m-zeroid structure. “It’s just mentioned and used,” he says. “After all, this is supposed to be an escape from the real world!”

“So say they want a fireball,” Palmatier explains. “They’d select the nodes for fire and shape and size and intensity and direction, etc., and when they’ve formulated exactly what they want, they end the ‘spell’ and the diamond implements the magic. Obviously there’s a power source behind all of this, but that’s the basic idea behind the ‘math’ side of the magic.”

Credits

Figure 1 is courtesy of Joshua Palmatier.

Author photo is by Igor Tolkov.