Common economic wisdom suggests that if markets are free to operate without intervention, the good times will roll. The recent world economic crisis, now sometimes referred to as the Great Recession, seems to suggest a more complex reality. Much of modern economics is based on the assumption that the "human actors" in the "economic drama" behave rationally. However, with the help of insights from the branch of mathematics known as game theory, some of the assumptions of modern economics can be seen as "simplistic." First, when people do act in what seems to be a rational way, they can wind up in a "bad place." Here we will take a look at a concept that has come to be called the "price of anarchy." The intuition here is that when rational people just do what they want, how bad can the result be compared with what could be achieved if they were "regulated" or "induced" into other behavior which is optimal (best)? Second, it may not be computationally easy to find one's way to a good place, whether it's an individual trying to get one's best outcome or a regulator who is trying to help the actors achieve their best outcomes.

I will be primarily concerned with situations that involve congestion, cars making independent decisions in situations such as how to get the fastest route from work to home in a road network, or the routing of packets of information on the internet. However, to begin let us consider the competitive situation below which is a well known example in mathematics, economics, political science, and psychology. It usually goes under the name of Prisoner's Dilemma.

Prisoner's Dilemma

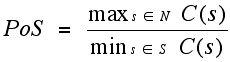

The name Prisoner's Dilemma is due to the mathematician Albert Tucker, who, though not the creator of this example, did much to popularize interest in it. It is one of many important games--including Chicken--which have been important both in the theory and application of game theory.

(Albert Tucker)

Here is the set-up, stripped of the setup that Tucker provided. Two individuals named Row and Column must each take one of two actions. Row has the choice of choosing either row I or row II, and Column, the other player, has the choice of column 1 or column 2. They act independently, and depending on the way they act, each of them gets a payoff, as indicated in the matrix (table) Table 1. For example, if Row picks row I and Column picks column 2 the result is a zero payoff (neither gain nor loss) to Row and a gain of 100 to Column.

| |

Column 1

|

Column 2

|

|

Row I

|

(80, 80)

|

(0, 100)

|

|

Row II

|

(100, 0)

|

(2, 2)

|

Table 1 (Payoff matrix for Prisoner's Dilemma)

You may be wondering if the players play the game only once, a fixed finite number of times, or a finite number of times but they don't know in advance how many times they will play. You may also wonder if they can talk to each other before they make their decision, what units the payoffs are in, and if they know their opponent. You may wonder if they can get a third party to keep them to their word if they are allowed to negotiate and lead their opponent to think they will act in a certain way.

What exactly do the payoff numbers represent? In a particular context, the number may mean the time it takes to drive to work or the number of dollars you collect from an opponent or from an "umpire." To generalize, mathematicians have developed a theory of "utility." Utility, measured in utiles, represents the amount of satisfaction one gets from the payoff. In games such as the ones we look at, the assumption is that people are rational when they try to get as much money or utility as possible or, for situations that get repeated, they try to maximize their average or expected utility (or money). Utilities can be negative; one can think of the payoff in this case as being something "painful" or unpleasant. Trying to maximize expected utility means that you record your payoffs over many plays of the game and take the mean of these numbers, the assumption being that you try to make this number as large as possible. (A different optimization function for utility would be to minimize the worst payoff that you might get. This approach is much studied, too - leave it to mathematicians to look at things from many different perspectives to improve the accuracy with which some real world phenomenon might be modeled.)

For simplicity, for Prisoner's Dilemma think of the payoffs as being in dollars. However, even for money there are subtle issues. Thus, finding a $20 bill on the street would have different meaning (utility) for different people according to their wealth. How will a rational player play this game? How would you play? Suppose you are Row. You might reason as follows: What would be best for me if I knew for sure what Column would do? Suppose you knew Column would play column I. Your answer would be to play row II. Why? If Column plays column 1, then if you play row I you get a payoff of $80, while if you play row II you get $100. More money looks more attractive. Now what would you do if Column played column 2? Again, you would play row II. The reason is that you would rather win $2 than win nothing. So, surely any rational Row would always play row 2. No matter what his opponent does he/she does at least as well. However, the payoffs in this game are completely symmetrical, which means that Column, if rational, would always play column 2. Hence, both of the players would wind up with small payoffs of $2 each by playing rationally, even though there is a collectively better outcome, a payoff of $80 for each if Row plays row I and Column plays column 1. The reason why Prisoner's Dilemma has commanded so much attention is the paradoxical consequence of seemingly rational analysis. Why not just tell/command Row and Column to play row I and column 1? The answer will turn out to lie with an insight of John Nash.

(John Nash)

This insight was not initially found for games such as Prisoner's Dilemma. It was an idea that emerged early in the history of zero-sum games (games for which the combined payoff for each outcome adds to zero for the players) via the concept of an equilibrium, i.e. the notation that from some point of view a way of playing the game was "stable." In a game played over and over again, a stable outcome is one where there are no incentives for a player to change behavior because doing so would not improve the player's payoff. The notion of an equilibrium has special important messages for games which are played repeatedly. The intuitive idea of an equilibrium is that if players are getting certain payoffs currently, in the most recent play of the game, then to switch the action that gives rise to that payoff does not make sense if there is reason to believe that the other players will not alter their play of the game and that a unilateral change diminishes one's payoff. Therefore, if changing one's action will only make matters worse if the other players don't change, why should one take a different action? Thus, if all players are in this same situation simultaneously, one might have reason to believe that in the next play of the game they will all act as they did on the previous play. This is the notion of an equilibrium position for a game.

The best known of the equilibrium concepts that can be used in the theory of games is due to the American mathematician John Nash. Nash was concerned with games of perfect information - games where all the players know all the actions they and their opponents can take and know the precise payoffs for any pattern of actions taken by the players. Nash established in 1951 that for games where each of the players has a finite number of actions each time the game is played, it has at least one mixed strategy equilibrium.

The difference between a pure strategy and a mixed strategy in games that are played a repeated number of times is that a pure strategy equilibrium arises when a player acts with the same choice of play each time the game is played. By contrast, a mixed equilibrium occurs when the players use randomization devices to play their different action choices in different amounts.

In the game in Table 2 clearly Row's playing a fixed row all the time when the game is played over and over again is not a clever idea. If Row plays row II all the time then Column always wins by playing column 1 all the time. (What should column always do if Row plays row I all of the time?)

| |

Column 1

|

Column 2

|

|

Row I

|

(1,-1)

|

(-1, 1)

|

|

Row II

|

(-1, 1)

|

(1, -1)

|

Table 2 (Payoff matrix for a "fair" zero-sum game)

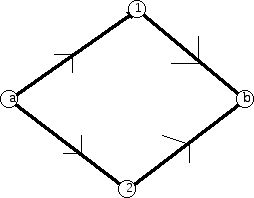

The optimal play for each of the players is to design a spinner in the spirit of the one shown below. Suppose Figure 1 represents Row's best mixed strategy spinner for a game. When the arrow is spun and if it lands in the region labeled Row I, then Row plays row I and similarly for row II. This spinner chooses row I and row II, three quarters and one quarter of the time, respectively. When the arrow lands on a line, spin it again.

Figure 1

Can you draw the spinners for Row and Column which are "optimal" for playing the game in Table 2? (The symmetry of the game in Table 2 may suggest the solution without doing a complicated calculation.)

Prisoner's Dilemma arises in so many applied settings that there are many books about Prisoner's Dilemma and variants of Prisoner's Dilemma. The reason that this game is so intriguing is that when a simple rationality principle is applied, it can lead to a "disastrous result." The model that has been created here is also over simplified from the point of view that the mathematical model incorporates the utilities of the players in the game but it does take into account in the analysis that there are results of the game which might have consequences for specific people and society in general in some versions of the game. For example, if the two players are nuclear superpowers and the game is played with the outcome of a nuclear war between the two superpowers, other people and countries have highly non-desirable effects from the game being played "rationally." Unfortunately, Prisoner's Dilemma is a reasonable model for some such nuclear confrontation games.

A central seminal example for probing further into these ideas is due to the German mathematician Dietrich Braess. This example probes the consequences of taking for granted that more choices automatically translate into improved service.

While the setup for what has come to be known as Braess's Paradox is somewhat limited and artificial, there are reasons to believe that the phenomenon described has happened in the "real world." Furthermore, it sets a basis for what can occur in more "realistic" situations.

Congestion models

Common sense suggests that if one has a road network which is currently congested, opening a new road should help. To understand what might go wrong, consider the following situation which may be an eye-opening example for seeing the subtleties of situations that economic planners and/or business executives might face. The issue is a real one in route planning for information packets traffic on the internet.

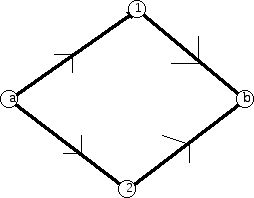

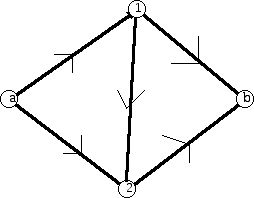

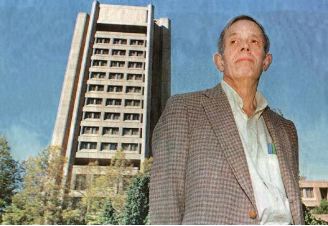

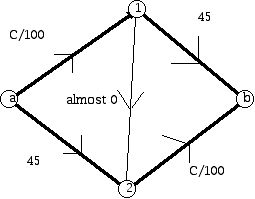

I will use the terminology of ordinary road traffic. The basic framework is that individual drivers are free to choose the route they want. In a very simple setting, the drivers all start at location a and have the goal of reaching location b. There is a network of roads which connect a and b and intermediate locations that drivers pass through on the way from a to b. The drivers are "rational" and they are information rich, that is, when they make a decision they know information about the state of the system and that other drivers have the same knowledge. The congestion on a piece of the road may depend on the number of cars that choose to travel that section of the road, or for some sections of road it may be independent of the number of cars. We will view there being a "cost" to the individual drivers and we can sum up the costs for the individuals to determine the cost to "society" of the decisions that are made by the individual drivers. From the viewpoint of the individual, congestion is related to the time it takes to get where he/she is going. (See Figures 2 and 3).

One can study the "equilibrium" time for a trip based on the current network and the choices made by the people who have to use the road network make. For a particular configuration of use, i.e., the choices made by the individuals, the group of drivers will collectively determine what is the outcome for the whole group. Assuming that each individual makes a rational decision given the information that he/she has available, what will occur? Then look at how the network changes by making a new road available. What can go wrong?

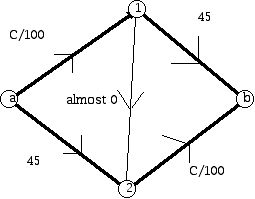

Figure 2 shows the geometry of the driving network initially, without any indication of the costs/times involved in traversing the network. Figure 3 shows the additional option in getting from a to b.

Figure 2

Figure 3

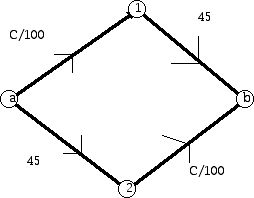

How long will it take to make the trip from a to b in the traffic networks shown in Figures 2 and 3? The amount of time will depend on things like the distances between the points involved, the state of repair of the roads, the amount of traffic on the roads, and perhaps other factors like the number of traffic lights, etc. For our purposes we will make some very strong modeling (simplifying) assumptions. We will assume that for some of the road sections the time involved is constant, while for other links the time is dependent on the number of cars using that link. Figure 4 shows the network given in Figure 1 with time costs attached to the edges involved.

Figure 4

The 45 on on the edges 1b and a2 means that regardless of the number of cars traveling those sections of the network, the time it will take those cars to travel that stretch will be 45 minutes. However, for the edges a1 and 2b the amount of time depends on the number of cars C traveling that section. Thus, if there were 500 cars traveling the stretch from a to 1, then the amount of time each car would need to get from a to 1 would be 500/100 or 5 minutes. If there were 1000 cars traveling from 2 to b, then it would take each of them 10 minutes to make the trip. (The cost functions chosen here are more to make certain points than to be realistic of an actual traffic situation.)

Suppose that there are 4000 cars, and each driver makes a decision about what route to take. Notice that from the point of view of each individual car the cost of traveling via a1b or a2b will depend only on how many other cars choose that route. It is not difficult to see that in this situation an equal number of cars on each of the two routes a1b and a2b would be an "equilibrium" in the sense that had any additional driver chosen the other route than the one he/she did, the choice would make his own costs go up. The division of the cars 2000 to a1b and 2000 to a2b is a Nash equilibrium, named for the American mathematician John Nash, who won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for his work. If even a single person changes his route, his or her time to get to the destination goes up, as does the total time for the whole group, though some people's times go down a small amount.

What is the time that each driver spends on the road when 2000 take the "high road" and 2000 take the "low road" ? The cost for each driver of a1 or 2b is the same: 2000/100 = 20 minutes and the cost of the 1b or a2 links is 45 minutes. Since each of the routes involves one 20-minute and one 45- minute link, the total time for each driver is 65 minutes each.

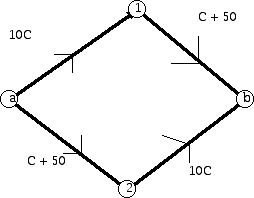

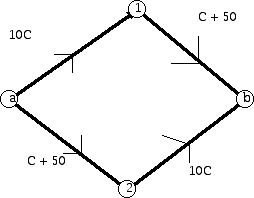

Now let us see what happens if an extra section of road is opened, as shown in Figure 5, with the cost of the added new road, designed to help with congestion being, "epsilon," a very small positive amount of time.

Figure 5

Suppose a driver was planning to use a1b. With the new arrangement she can do better by using a12b. Similarly, a driver planning to use a2b would now prefer to use a12b. In fact, this reasoning applies to all 4000 drivers. In this new system everyone will select a12b! How much time will this mean for each individual's trip? The cost for each driver using a1 is 4000/100 = 40 minutes while road 12 costs virtually no time at all, and road 2b costs 4000/100 = 40 minutes. Thus, the total trip takes 80 minutes plus the small amount, epsilon.

Paradoxically, opening the link to cut down on congestion creates longer trips for all rational players. Note that if 4000 drivers are using a12b, then if a driver decides to use a2b instead, he/she needs 45 + 40 minutes, which is 85 minutes for his/her trip, which makes matters worse. (The cost to the other drivers who follow a12b is cut down a small amount since now there will be 3999 drivers who have a trip lasting 3999/100 + 0 + 4000/100 = 39.99 + 40 = 79.99 minutes.)

The idea behind this has become known as Braess's Paradox, named for the mathematician Dietrich Braess, who first observed that this kind of behavior can happen. This paradox has things in common with examples of paradoxical games such as Prisoner's Dilemma and Chicken. Games of this kind have the property that rational behavior on the part of the players results in an outcome which is not in the best interests of any of the players.

The implications and ramifications of Braess's Paradox have been explored in many directions. It has become a poster child for examining to what extent allowing individuals to do as they please results in a penalty for the group of which the individuals are a part. Many argue that if markets are allowed to be totally free, the result will be favorable outcomes for the people who participate in these markets. However, the example of Braess shows that this need not be true. If there were a "regulator" who could help assist the individuals in making their decisions by telling them which route would be good for them and these recommendations were binding, then one can look at some measure of the improvement that having regulation gives over total freedom. There is a variety of such measures but one natural such measure is known as the price of anarchy. This phrase as informally described above is due to the theoretical computer scientist Christos Papadimitriou (U. California-Berkeley). There is a large literature of examples and theory related to extensions of Braess's paradox and associated issues involving the price of anarchy. Intuitively, the issue is how large the cost can be if one lets rational people do what they want in various situations!

There are two natural measures of "social welfare" in situations of this kind. For each individual we can compute the utility for the individual of a particular solution. Thus, given player x, the utility for x could be denoted u(x).

One social optimum would be to find a solution where one maximizes the sum of u(x) over all choices of players x involved. This is usually referred to as the utilitarian solution. People who are often associated with this point of view were Jeremy Bentham (1748-1842) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), and in more modern times, Peter Singer. The main idea is to secure the most good for the most people in the group. Another approach is to find a solution which maximizes the minimum value of u(x) for the players involved. This approach is sometimes known as egalitarianism. A philosopher associated with this viewpoint is John Rawls (1921-2002). Note that it is entirely possible to have an overwhelming part of one's population be very "unhappy" if there is a small group of people who are given huge amounts of utility and the goal is maximizing total utility. Rawl's point of view often precludes solutions of this type.

If you want some practice for the ideas presented here, consider the next two networks (with different cost functions than above) where there are 6 drivers. What is the best behavior for the six drivers in Figure 6 below?

Figure 6

Now, a new road is opened (Figure 7). Now what is the best behavior for the 6 drivers?

Figure 7

This circle of ideas is a lovely environment to show how using simple analytical skills gives one insight into many phenomena arising in daily life, economics, and the business world.

Braess's Paradox

Dietrick Braess (Oberwolfach Photo Collection)

Braess's original paper appeared in German in 1968, under the title: Über ein Paradoxon aus der Verkehrsplanung. Unternehmensforschung (Translation: A paradox of traffic planning).

While initially Braess's example was treated as a curiosity and as a "paradox" in the spirit of many famous paradoxes of the past: Russell's Barber Paradox or the Hilbert Hotel, it was soon realized that "real world" examples of the behavior implicit in the example actually occurred. Furthermore, with the development of the field of algorithmic game theory, the branch of mathematics and computer science which deals with the study of computational and algorithmic aspects of game theory, the central role of Braess's paradoxical example for a variety of central problems became clear.

What Prisoner's Dilemma and Braess's Paradox point out is that there are situations where, if individuals are left to make their own decisions, the result might be that as a group or as individuals they are worse off.

The price of anarchy

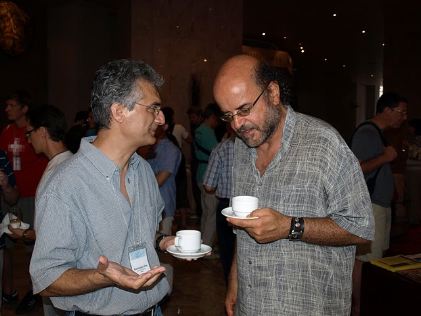

The study of the price of anarchy was initiated by Christos Papadimitriou and Elias Koutsoupias in a paper which appeared in 1999. Koutsoupias writes: "At the time, we called it 'coordination ratio', but later Christos coined the catchy term 'price of anarchy'." The catchy term may have helped because there are now hundreds of scholarly articles which make reference to this idea or have extended the concept.

(Photo courtesy of Elias Koutsoupias (left) and Christos Papadimitriou (right))

The essential idea here is to see how poor an outcome one can get in a competitive situation (congestion game, routing internet packets, machine scheduling, etc.) when the players act rationally and in their own interests, versus the optimal that can be obtained for the same situation assuming that the players can agree or be forced/induced to behave in a way that may seem to be "poor" but, because it is imposed in a way that takes other people's behavior into account, is better collectively.

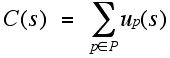

The formal definition of the price of anarchy works as follows. For each outcome of the game we consider the sum of the utilities of the players when this outcome occurs. Now we can compute the utility for "society" - all of the players for each of the Nash equilibra of the game - and see which gives the best result for the players. Finally, we can also compute the utility for all of the players which is largest, whether or not it is a Nash equilibrium.

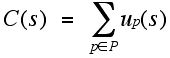

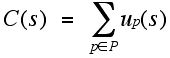

To express the concept of the price of anarchy in more formal terms we can introduce the following notation. P will denote the collection of players in the game and S the set of outcomes. (If there are n players in P, then S will consist of the n-tuples, each entry in the n-tuple being the payoff to one of the n players.) W will denote the "welfare" associated with a particular outcome. Hence, given an outcome s, we have:

In words, this says that if we take player p from the set of players, p has a certain utility, and for a particular outcome s we can get the utility of all the players represented in s by adding up their individual utilities. (There are other alternatives for how to compute the welfare associated with an outcome s. A common alternative would be to choose the minimum utility of any of the players as a measure of the welfare of the outcome.) Thus, for example, if two players in a game have the payoff pair (3, 6), the value of W(3, 6) associated with this outcome would be 9. (If we had chosen as the measure of welfare the minimum of the players' outcomes, the value would be 3.) I will use N to denote the set of Nash equilibria, but in some situations one may use a different equilibrium concept other than the Nash equilibrium. Note that N is a subset of the set S of outcomes - those outcomes which correspond to Nash equilibria. We can now define the Price of Anarchy, PoA:

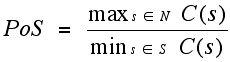

In short, we are taking the ratio of the best (optimal) regulatory solution and the worst possible equilibrium solution. In some kinds of problems where we are concerned not with the "welfare" the system is delivering but with its efficiency, the formulation is taken a bit differently. In the welfare setting we are trying to maximize the "welfare." However, if we are trying to measure not welfare but efficiency, we wish to have some "cost" minimized. Now, we interpret the payoffs as costs, so we have the revised PoA measure:

where:

This form of the price of anarchy idea would be utilized for games where the messages (information packets) are being transmitted and one is interested in how much delay is occurring in the arrival of the message or packet.

For the Prisoner's Dilemma game in Table 1 (copied below) we have the value in the numerator is 160 (80 + 80) and the value in the denominator is 4 (2 + 2), so the the price of anarchy using (first form above) is 40. However, we can make PoA arbitrarily large for a sequence of Prisoner's Dilemma games. This suggests that perhaps it is not wise to let people try to play this kind of game without some kind of external "controls."

| |

Column 1

|

Column 2

|

|

Row I

|

(80, 80)

|

(0, 100)

|

|

Row II

|

(100, 0)

|

(2, 2)

|

The power of introducing new "measures'" such as the price of anarchy is that it makes it possible to quantitatively compare different situations and to focus questions about a particular game or class of games. For example, one might be willing to live with a situation where the price of anarchy was relatively small because it meant that even in the worst case allowing people to make choices freely could not be much improved upon.

The price of anarchy concept has resulted in a wide variety of new applied and theoretical developments. In particular, there has been a tremendous amount of research into "congestion games." These games inspired by models which jump off from the Braess "Paradox" discussed above and routing of information packets from cell phone traffic, internet traffic, etc. are important because we would all like to have reliable and fast delivery of such "messages." The players in such games may be individuals such as you and me or the phone companies and internet providers. From the point of view of you and me we may accumulate some of our information services to weekends or evenings to avoid charges that apply during daytime. This rational behavior runs the risk of slowing down service over what might occur if we all just sent messages when it occurred to us to do so, independent of cost issues.

Inspired by the concept of the price of anarchy researchers have explored other related concepts. One example is the price of stability. The goal here is to get insight into the tradeoff in a game between the best (optimal) optimal outcome for the players of the game compared with the outcome that achieves "stability."

The analogous equations here to the ones above are:

and

where the first equation computes the cost of a particular outcome and the second finds the price of stability.

These ideas are being pursued actively by both mathematicians and computer scientists. In fact, there is a new field within game theory (initially developed in mathematics) concerned with computational issues in game theory, known as algorithmic game theory. This branch of computer science (and mathematics) aims to understand computational complexity issues involved in game theory as well as to design better algorithms for computing quantities (strategies) of interest to game theorists. There have been many breakthroughs in the last several years in this rapidly emerging area. For example, Nash's original proof that games have Nash equilibria depended on the use of the fixed point theorem of Brouwer. His proof was an existence proof and did not actually give algorithms for finding equilibria in games. The question arose how the complexity of computing Nash equilibria compared with complexity issues involved in fixed point computations. If economic problems require human beings to find (compute) Nash equilibria in complex games to play the games "well," then it becomes important how hard it is computationally to do this. Recent complexity results suggest that it is very hard to "learn" one's way to these equilibria. Other results show the range of values that the price of anarchy can take on for a wide variety of networks that differ greatly in their structure. Recent work has been done for various types of games to determine which structures will guarantee that selfish players achieve their optimal outcome at a Nash equilibrium.

What is going on here is that fast-changing aspects of technological innovation are driving theorists to assist the process of guiding the technological innovations. The theory often makes clear that innovators can't achieve certain goals, even though they might hope to.

Mathematics and theoretical computer science grow both in response to their own internal investigations and to attempts to model the world in which we live. This interplay of pure and applied work is candy for the mind and makes our world a better and richer place.

Bibliography

Anshelevich, E. and A. Dasgupta, J. Kleinberg, E. Tardos, T. Wexler, and T. Roughgarden, The price of stability for network design with fair cost allocation. In Proc. 45th Symposium Foundations of Computer Science, pp. 295-304, 2004.

Braess, D., Über ein Paradoxon aus der Verkehrsplanung. Unternehmensforschung 12, 258-268 (1968) (On a paradox of traffic planning. (joint translation of the German original with Anna Nagurney, Tina Wakolbinger), Transportation Science 39, 446-450 (2005))

Cohen, J., The Counterintuitive in Conflict and Cooperation, American Scientist 76 (1988) 576-584.

Cohen, J. and P. Horowitz, Paradoxical behavior of mechanical and electrical networks, Nature, 352 (1991) 699-701.

Christodoulou, G. and E. Koutsoupias, The price of anarchy of finite congestion games, Proc. 37th Symposium on Theory of Computing, pp. 67-73, 2005.

Correa, J. and A. Schulz, N. Moses, Selfish routing in capacitated networks, Math. Operations Res., 29 (2004) 961-976.

Epstein, A. and M. Feldman and Y. Mansour, Efficient Graph Topologies in Network Routing Games, In Joint Workshop on Economics of Networked Systems and Incentive-Based Computing, 2007.

Fabricant, A. and C. Papadimitrious, K. Talwar, The complexity of pure nash equilibria, Proceedings of STOC 04, 2006, pp. 604-612.

Fadel, R. and I. Segal, The communication cost of selfishness, J. of Economic Theory, 2008.

Koutsoupias, K. and C. Papadimitriou. Worst-case equilibria. In STACS, 1999, pp. 404–413.

Mavronicolas, M. and P. Spirakis, The price of selfish routing, 33rd STOC, 2001, pp. 510-519.

Nisan, N. and A. Ronen, Algorithmic mechanism design, Games and Economics Behavior, 35 (2001) 166-196.

Nisan, N. and T. Roughgarden, E. Tardos, V. Vazirani (eds), Algorithmic Game Theory, Cambridge U. Press, New York, 2007.

Papadimitriou, C. and T. Roughgarden, Computer correlated equilibria in multi-player games, Journal of the ACM, 2008.

Roughgarden, T., Designing networks for selfish users is hard, Proc. 42nd Symposium Foundations of Computer Science, 2001, pp. 472-481.

Roughgarden, T., The price of anarchy is independent of the network topology, J. Comput. System Science, 67 (2003) 341-346.

Roughgarden, T., Selfish Routing and the Price of Anarchy, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2005.

Roughgarden, T., Selfish routing with atomic players, In SODA 16, 2005, pp. 1184-1185.

Roughgarden, T. and E. Tardos, How bad is selfish routing? J. ACM, 49 (2002) 236-259.

Smith, M., The existence, uniqueness and stability of traffic equilibria, Transport. Res., Part B, 13 (1979) 295-304.

Note:

In 2006, the University of Massachusetts Amherst held a seminar to celebrate the translation into English of Braess’s landmark 1968 article. See photos from the event and link to slides from his talk.

Blogs treating recent developments in algorithic game theory and related mechanism design questions are:

http://agtb.wordpress.com/

(maintained by Noam Nisan)

http://marketdesigner.blogspot.com/

(maintained by Alvin Roth)

Those who can access JSTOR can find some of the papers mentioned above there. For those with access, the American Mathematical Society's MathSciNet can be used to get additional bibliographic information and reviews of some of these materials. Some of the items above can be accessed via the ACM Portal, which also provides bibliographic services.

Joseph Malkevitch

Joseph Malkevitch