Primes

3. Distribution of the primes

Mathematicians certainly like to count things. One natural focus of attention about primes is: Can one be precise about the statement that as numbers get larger, the number of primes seems to thin out?

Here is a small table showing information about the primes:

|

Range of integers:

|

Number of primes |

Number of twin primes |

|

301-400 |

16 |

2 |

|

601-700 |

16 |

4 |

|

2801-2900 |

12 |

1 |

|

2901-3000 |

11 |

1 |

|

10301-10400 |

12 |

2 |

This small sample of data is typical of the complex behavior of the "distribution" of primes. The hunch that as one gets further out in the integers the primes are less "dense" and the appearance of twin primes becomes more rare, is borne out. However, we see from the table that the distribution of primes is very complex. Yet mathematicians have remarkable results about the distribution of the primes.

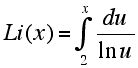

Two early attempts to chart the distribution of the primes were made by Adrain-Marie Legendre (1752-1833) and by Carl Friedrich Gauss. To understand what was accomplished let us define the function π(x) which for a given positive number x gives the number of primes which do not exceed x. In a book written in 1798, Legendre suggested that π(x) is given approximately by x/(ln x - 1.08366). Here ln x is the natural logarithm ofx. Gauss not only noticed the relation between π(x) and x/(lnx) but also between π(x) and an integral formula:

What seemed to be the case was that as x got larger, the ratio between π(x) and x/(ln x) got closer to 1. This result is known today as the Prime Number Theorem. To provide two data points, when x is a million, x/(ln x) is about 72,382, while π(x) is 78,498, and for a billion the corresponding values are 48,254,942 and 50,847,534. Thus,x/ln(x) gives an increasingly good estimate for π(x). For a billion, the estimate is off by about 5 percent.

Although in essence Gauss conjectured the Prime Number Theorem, he was unable to prove it. A rigorous proof proved to be elusive. Important progress was made by the Russian mathematician Chebyshev, who showed that there were constants a and b so that:

ax/(ln x) < π(x) < bx/(ln x).

However, the Prime Number Theorem was first proved independently in 1896 by the French mathematician Jacques Hadamard (1865-1962) and the Belgian mathematician Charles de la Vallée Poussin (1866-1962). (Not only did these men provide independent proofs, but they were born a year apart and died in the same year.) The proof techniques that were used involved the theory of functions of a complex variable. Eventually, a proof (1949) of the Prime Number Theorem which did not involve the use of the theory of complex functions was given by Paul Erdös and Atle Selberg. We see here a classic example of how long it sometimes takes to give a rigorous proof of a mathematical result which "empirically" was known for a long time. Still unresolved was the honing of powerful conceptual tools that made it possible to provide a proof and to get additional structural insights as well. Researchers are still trying to get new and different insights into the distribution of the primes.

-

Introduction

-

Basic ideas

-

Distribution of the primes

-

Complexity and algorithms

-

Primes and cryptography

-

The right stuff

-

References

Welcome to the

Feature Column!

These web essays are designed for those who have already discovered the joys of mathematics as well as for those who may be uncomfortable with mathematics.

Read more . . .

Feature Column at a glance