Percolation: Slipping through the Cracks

Posted August 2008.

The existence of a critical probability makes percolation a mathematically interesting and rich subject. ...

David Austin

Grand Valley State University

david at merganser.math.gvsu.edu

Introduction

My backyard has an area where the soil is mainly clay and another where it's mainly sand. The day after a hard rain, the sandy region is usually dry while the clay region is still damp. The process by which water moves through a medium, like sand or clay, is called percolation and is currently the focus of significant mathematical activity, some of which we'll describe in this article.

Geoffrey Grimmett begins his book Percolation with the question: "Suppose we immerse a large porous stone in a bucket of water. What is the probability that the centre of the stone is wetted?" To begin creating a mathematical model, we will imagine a two-dimensional lattice of channels running through the rock (a more realistic three-dimensional model can wait).

This is known as the square lattice, and we will denote it by Z2. We choose a parameter p between 0 and 1 and declare that each edge is open with probability p. Think of an open edge as a channel that is large enough to conduct water through it. Here are examples for two different values of p.

| p = 0.3 |

p = 0.6 |

|

|

If we imagine that the size of the channels is much smaller than the size of the rock, it is reasonable to assume that the lattice is infinite in extent. To rephrase Grimmett's question, we may ask, "What is the probability that there is a path of open edges from the origin that travels infinitely far?

We can easily make two statements. When p = 0, every edge is closed so there will be no infinite open path containing the origin. However, when p = 1, every edge will be open so there must be an infinite open path.

What happens for intermediate values of p? For small p, there will be few open channels so any open paths will most likely be short. However, as p increases, there are more open channels, and eventually it is likely that there is an infinite open path starting at the origin. If there is a positive probability of having such an infinite path, we say that percolation occurs. We will see that there is a critical probability, that we denote pc, representing a threshold; percolation occurs above pc but not below. A result due to Harris and Kesten, which we'll outline later, states that the critical probability for the square lattice is pc = 1/2.

The existence of a critical probability makes percolation a mathematically interesting and rich subject. On either side of the critical probability, the system behaves in fundamentally different ways (as water drains easily through sandy soil but not through clay). As such, it serves as a model for more complex systems that experience a phase transition when some parameter, such as temperature, passes through a critical value. Percolation provides a model that is simple enough to be mathematically accessible while still displaying many of the features of more complex systems.

A simple example

Let's begin with a simple example that illustrates some general principles. We will study percolation on the infinite binary tree, a portion of which is shown below.

If p is the probability that each edge is open, we want to find θ(p), the probability that there is an infinite open path containing the root of the tree v0. We begin by letting Pn be the probability that there is an open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below. Notice that we have P0 = 1. Shown in red below is a path from v0 to a vertex three levels below.

This path moves through another vertex v1. The probability that an open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below passes through v1 is pPn-1, the probability p that the edge from v0 to v1 is open times the probability Pn-1 that a path from v1 to a vertex n - 1 levels below it is open. Therefore, the probability that there is no open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below passing through v1 is 1 - pPn-1.

This path moves through another vertex v1. The probability that an open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below passes through v1 is pPn-1, the probability p that the edge from v0 to v1 is open times the probability Pn-1 that a path from v1 to a vertex n - 1 levels below it is open. Therefore, the probability that there is no open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below passing through v1 is 1 - pPn-1.

Since any path from v0 to a vertex n levels below must pass through one of the children of v0, we find that the probability that there is not an open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below is

and therefore

If we define the function fp(x) = 1 - (1 - px)2, we have Pn = fp(Pn-1). The graph of fp is shown below in two different cases, depending on the derivative fp'(0) = 2p.

|

fp'(0) = 2p > 1

|

fp'(0) = 2p < 1

|

|

|

In the first case, 2p > 1 , we see that there is a fixed point

and if 2p < 1, the only fixed point is x0 = 0.

From the graph, we see that if 2p > 1 and x > x0, then x0 < fp(x) < x. Since P0 = 1, we have

| |

|

|

and

|

|

|

and so on.

|

It then follows that

if p > 1/2. The graph of θ(p) is therefore shown below:

Here we see that the critical probability, pc = 1/2; above pc, θ(p) > 0 and we have percolation. Below the critical probability, θ(p) = 0 and there is no percolation.

This example is unusual in that it is difficult to compute the critical probability and θ(p) exactly for most combinatorial graphs. As we'll see toward the end of this article, however, it is thought that the specific form that θ(p) takes here shares features with that from other graphs.

Percolation on the square lattice

Percolation theory was introduced to mathematicians by Broadbent and Hammersley in 1957. For two decades, work in this new field concentrated mainly on finding critical probabilities. For instance, Broadbent and Hammersley showed that the critical probability for the square lattice Z2, shown below, is between 1/3 and 2/3.

On the basis of Monte Carlo simulations, Hammersley later suggested that this probability should be 1/2. Indeed, through work of Harris and later Kesten, it was eventually proven that pc = 1/2. We will outline the proof of this theorem later. For now, let's develop a feel for how configurations behave for various values of p.

Here is one configuration of open edges that results when p = 0.4.

Given a configuration of open edges and a vertex v in the lattice, the cluster Cv will denote the collection of vertices connected to v by open edges.

Below we show a configuration when p = 0.3 and C0, the cluster containing the origin, in blue.

Remember that θ(p) is the probability that there is an infinite path containing the origin, which is the same event as the cluster C0 being infinite. Here's what happens as we increase p.

| p = 0.2 |

p = 0.3 |

|

|

| p = 0.4 |

p = 0.45 |

|

|

| p = 0.5 |

p = 0.55 |

|

|

| p = 0.6 |

p = 0.8 |

|

|

Based on these examples, two things can be observed. First, if we look at a fixed value of p, we see that the size of the clusters is relatively small for small values of p. A theorem of Menshikov allows us to state this quantitatively.

If E is some event, we will use Pp(E) to denote the probability that E holds when the edges are open with probability p. By Sx,n, we will denote the event that there is an open path from a vertex x to another vertex whose distance from x, measured in the lattice, is n. (We measure distances in the lattice as the number of edges in the shortest possible path between the two vertices.) Though proven in considerably more generality, Menshikov's theorem roughly says that

|

For a given p < pc, there is a constant a such that P(Sx,n) ≤ e-an.

|

This means that the probability of having an open path decreases exponentially as the distance traveled by the path increases.

The Harris-Kesten Theorem

For our second observation, imagine increasing p as we consider the size of the cluster C0. It is relatively small for small values of p, but around p = 0.45, its size begins to grow significantly. This leads us to suspect that the critical probability pc, the probability that marks the transition from θ(p) = 0 to θ(p) > 0 occurs around 1/2.

In fact, one of the first significant results in percolation theory is the Harris-Kesten Theorem

|

For the square lattice, pc = 1/2.

|

In what follows, we will outline a proof of this theorem, which divides naturally into two parts. The first half, originally proven by Harris in 1960, states that θ(1/2) = 0. In particular, this implies that pc ≥ 1/2. The second half, proven later by Kesten in 1982, says that pc ≤ 1/2. The result that pc = 1/2 naturally follows.

We'll begin outlining an argument for Harris' theorem by considering the dual of the square lattice. This graph is formed from the square lattice by placing one vertex in the center of each square and joining vertices with an edge when their corresponding squares in the square lattice share an edge.

Notice that if we are given an edge in the lattice, there is exactly one edge crossing it in the dual. Also, the dual lattice is a copy of the square lattice translated so that the vertices are in the centers of the squares. For this reason, we say the square lattice is self-dual.

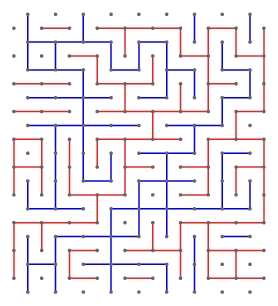

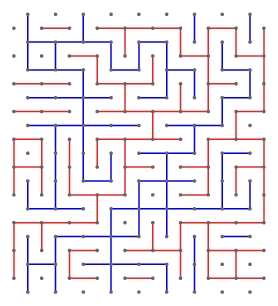

Suppose we are given a configuration of open edges in the square lattice. We will consider an edge in the dual lattice to be open exactly when the edge it crosses in the square lattice is closed. Shown below in red is a configuration for the square lattice and, in blue, the corresponding configuration in the dual lattice.

In this way, requiring that the edges in the square lattice are open with probability p is the same as requiring that edges in the dual lattice are open with probability 1 - p.

Now consider C0, the cluster in the square lattice containing the origin. If p < pc, then this cluster is almost surely finite. As the figure below shows, this means that there is almost surely an open cycle in the dual lattice containing the origin in its interior (shown in green).

To summarize, we see that θ(p) = 0 for those values of p for which there is almost surely an open cycle in the dual lattice containing the origin in its interior. We will therefore assume that p = 1/2 and show that there is almost surely an open cycle in the dual lattice containing the origin in its interior. From this it follows that θ(1/2) = 0 and hence pc ≥ 1/2.

To do this, we will find the probability that there is an open cycle in the dual lattice contained in an annulus and composed of four separate open paths as shown below.

Breaking the problem down even further, we will look at one of the four sides of this rectangular annulus, a rectangle whose dimensions are 3n by n, and find the probability that there is an open path running horizontally across this rectangle. We begin, however, by studying a square.

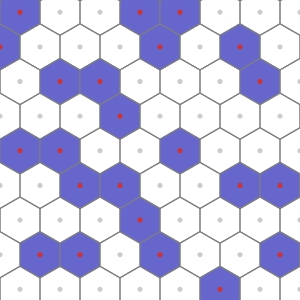

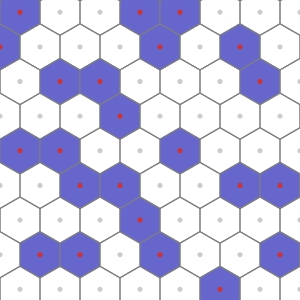

Here is a fundamental observation: Suppose we consider R, a rectangular portion of the square lattice with k by l vertices. We may also consider R', a k - 1 by l + 1 rectangular portion of the dual lattice:

|

We will show that there is either an open path moving horizontally across R or there is an open vertical path in R'. To see this, imagine constructing the figure on the right: there is a hexagon on each vertex in R and R'. Hexagons corresponding to vertices in R are shaded. The squares between hexagons correspond to edges, and these are shaded if the corresponding edge is open in R (and hence closed in R'). White squares therefore correspond to open edges in R'. Since we are interested in horizontal open paths in R, we consider all the edges on the left and right sides to be open. Similarly, we consider all edges at the top and bottom to be open in R'.

|

|

|

Imagine that we start at the corner A and walk on the border between the white and gray regions. This path may only end at B or C since the gray region is always on our right.

|

|

|

If we end at B, we have a horizontal open path across R,

|

|

|

and if we end at C, we have a vertical open path across R'.

|

|

Recall that Pp(H(R)) denotes the probability that there is a horizontal open path across R when edges are open with probability p. In the same way, P1-p(V(R')) is the probability that there is an open vertical path across R'.

Since there is either a horizontal open path across R or an open vertical path across R', we must have

| |

|

|

and so

|

|

If we consider the case that R is an n + 1 by n rectangle, then R' is an n by n + 1 rectangle. We then have P1/2(H(R)) = P1/2(V(R')) = 1/2. If instead we take R to be an n by n square S, a horizontal path has a shorter distance to travel so we have

Notice that this is independent of n, the size of the square.

Now that we understand the probability of having an open path across a square, we would like to use this understanding to study more general rectangles. Remember that we would eventually like to understand rectangles of dimension 3n by n. The following technique is due to Russo, Seymour and Welsh.

Consider the figure to the left, in which we have two squares of sides n and 2n. Consider the event F1 described by a configuration of open paths, like the blue and red ones shown below. We know that the probability of an open vertical path in the smaller square is greater than 1/2. In the same way, the probability of having a horizontal path, like the red one, open is greater than 1/2 as well. The fact that we want the red path to enter the smaller square introduces another factor of 1/2:

Consider the figure to the left, in which we have two squares of sides n and 2n. Consider the event F1 described by a configuration of open paths, like the blue and red ones shown below. We know that the probability of an open vertical path in the smaller square is greater than 1/2. In the same way, the probability of having a horizontal path, like the red one, open is greater than 1/2 as well. The fact that we want the red path to enter the smaller square introduces another factor of 1/2:

Now let F2 be the event that there is an open path across a 3n by 2n rectangle. We break this into smaller pieces by considering the rectangle to consist of two squares of dimension 2n by 2n overlapping in an n by 2n rectangle. Applying our previous result, we have

Now let F2 be the event that there is an open path across a 3n by 2n rectangle. We break this into smaller pieces by considering the rectangle to consist of two squares of dimension 2n by 2n overlapping in an n by 2n rectangle. Applying our previous result, we have

Continuing in this way, we may continue to understand wider rectangles by breaking them into smaller rectangles that overlap in a square. For instance, the figure to the right illustrates an argument showing that the probability there is an open path across a 2n by n rectangle is greater than 2-15.

Continuing in this way, we may continue to understand wider rectangles by breaking them into smaller rectangles that overlap in a square. For instance, the figure to the right illustrates an argument showing that the probability there is an open path across a 2n by n rectangle is greater than 2-15.

With some additional work, we see that the probability that there is an open horizontal path across a 3n by n rectangle is greater than 2-25.

Remember that we are interested in finding an open cycle around the annulus shown below. Decomposing the annulus into four rectangles whose dimensions are 3n by n, we see that the probability of having an open cycle in the annulus is greater than (2-25)4 = 2-100. That's a pretty small number, but it's enough to do the trick. Again, the important point is that this number does not depend on the size of the annulus.

We now imagine ringing the origin with a set of concentric annuli as shown.

We now know that the probability there is no open cycle in an annulus is smaller than 1 - 2-100. Therefore, if we look at k concentric annuli, the probability that there is an open cycle encircling the origin is smaller than (1 - 2-100)k. Since 1 - 2-100 < 1, we see, by allowing k to become arbitrarily large, that the probability that there is no open cycle encircling the origin is smaller than any positive number and hence zero. Therefore, there is almost surely an open cycle encircling the origin, which means that C0 is almost surely finite and hence θ(1/2) = 0 and pc ≥ 1/2. This completes the proof of Harris' Theorem.

To complete the proof of the Harris-Kesten theorem, we also need to prove Kesten's theorem, which says that pc ≤ 1/2. We will do this by assuming that pc > 1/2 and arriving at a contradiction. The argument sketched here is not Kesten's original proof.

If we assume that pc > 1/2, then p = 1/2 is below the critical probability. Recalling Menshikov's theorem, which we stated earlier, we then have

|

P1/2(Sx,n) ≤ e-an, for some constant a,

|

where Sx,n is the event that an open path runs from x to a vertex whose distance from x is n.

Consider an n by n square S. Since there are n vertices on the left side of the square and any horizontal path has length at least n - 1, we have

By choosing n to be very large, we can make the term n e-an as small as we like. For instance, we may choose n to be so large that n e-an < 1/4. The inequality above then says that P1/2(H(S)) < 1/4. However, this contradicts the fact that P1/2(H(S)) ≥ 1/2. Therefore, our assumption that 1/2 < pc must be incorrect, which completes the proof of Kesten's theorem.

Some other results

The early days of mathematical work in percolation focused on finding critical probabilities for various combinatorial graphs. After a considerable amount of effort, relatively little is known. Here is a summary.

The scenario we have presented, where edges are declared to be open or closed, is usually known as bond percolation. Alternatively, we may also consider site percolation, in which the vertices of the graph are declared to be open with probability p. We then study paths in which every vertex visited is open.

Shown below, for instance, are the vertices in the triangular lattice T and a configuration of open vertices with p = 0.3.

|

We may consider replacing the vertices by hexagonal tiles, coloring the open ones, and asking if there is an infinite connected set of colored tiles. In 1982, Kesten proved that pc = 1/2 for site percolation on the triangular lattice.

For bond percolation on the triangular lattice, Wierman showed in 1981 that pc = 2 sin(π/18) ≈ 0.347. It should not be surprising that this critical probability for bond percolation is lower than that for the square lattice since each vertex in the triangular lattice has six edges compared to four in the square lattice.

|

|

Since the triangular lattice T is dual to the hexagonal lattice H, it is not surprising that the critical probability for bond percolation on H is pc = 1 - 2 sin(π/18).

|

Aside from these results and those for regular graphs, which are similar to the binary tree we looked at earlier, very little is known about the exact values of critical probabilities for other graphs.

Conformal Invariance

As mentioned before, early work in percolation theory concentrated on finding critical probabilities. Recently, however, theoretical physics has raised interesting questions in some different directions.

It should be clear that the critical probability depends on geometric properties of the graph. However, there is evidence that certain percolation probabilities remain unchanged under "conformal maps."

A conformal map of the plane is a function from one region in the plane to another that may distort distances but must preserve angles. Examples are provided by complex analytic functions such as f(z) = ez. Motivated by theoretical physics and numerical experiments, Aizenman and Langlands, Pouliot and Saint-Aubin conjectured that certain "crossing probabilities" were unchanged after the application of a conformal map, as we'll now explain.

To begin, we will consider a region D in the plane with four marked points P1, P2, P3, and P4. These points divide the boundary of D into four arcs A1, A2, A3, and A4. We will call this data a 4-marked region and denote it by D4.

If L is some lattice in the plane, we may consider the portion inside D and a configuration in which either sites or bonds are open with probability p.

By P(D4,L, p), we mean the probability that there is an open crossing from arc A1 to A3 contained inside D. The example P(H(R)) that we considered earlier is a special case of this construction.

Finally, imagine that the lattice L is scaled by a parameter δ to obtain δL. Here are some examples:

|

δ = 0.5

|

δ = 0.25

|

|

|

Consider what happens as δ → 0. Since the distance between the two arcs in δL grows arbitarily large and, if p < pc, Menshikov's theorem says that the size of the clusters decays exponentially, we must have P(D4, δL, p) → 0 if p < pc.

Conversely, if p > pc, we are guaranteed to have an infinite cluster, and it follows that P(D4, δL, p) → 1.

The interesting question is what happens if p = pc.

|

Conjecture (Aizenman and Langland, Pouliot, Saint-Aubin):

|

|

For any "reasonable" lattice L, the limiting probability

exists, lies in the open interval (0, 1) and is independent of the lattice L.

Moreover, if D4' is the result of applying a conformal map to D4, then P(D4) = P(D4').

|

This is a remarkable conjecture for it says that the limiting probability does not depend on the lattice and is unchanged when the region is changed by a conformal map. In fact, Cardy, motivated by ideas from conformal field theory, proposed an exact formula for the limiting probability.

To understand Cardy's formula, we note that conformal maps provides a great deal of versatility. For instance, any two regions D3 with three marked points are related to one another by a conformal map, a fact that follows from the Riemann mapping theorem. If we consider a 4-marked region D4 and momentarily forget about the fourth point P4, there is then a conformal map carrying the region D and the three marked points P1, P2, and P3 into the equilateral triangle D' with vertices P'1 = (1, 0), P'2 = (1/2,  /2), and P'3 = (0, 0). Now the fourth point P4 corresponds to a point P'4 = (x, 0) as shown below.

/2), and P'3 = (0, 0). Now the fourth point P4 corresponds to a point P'4 = (x, 0) as shown below.

Assuming that conformal invariance holds, Cardy's remarkable formula, interpreted in this way, says that P(D4) = x. As yet, conformal invariance and Cardy's formula have only been rigorously proven for the case of site percolation on the triangular lattice T, a result due to Smirnov in 2001. However, there is considerable evidence to suggest that they hold in wide generality.

Power laws and universality

Theoretical physics also predicts that a number of properties depend, not on the geometric properties of the graph, but only on its dimension. For instance, we know that the critical probability for site percolation on the triangular lattice is 1/2. This says that θ(p) = 0 for p < 1/2. If, however, we ask how θ(p) behaves for values of p above 1/2, physics indicates that the following should hold:

|

θ(p) ≈ (p - 1/2)5/36 for values of p just above 1/2.

|

We call such an expression a power law. Besides demonstrating the relatively simple behavior of θ(p) in the case of site percolation on the triangular lattice, the conjecture further says that the exponent 5/36 should describe θ(p) for percolation on any planar lattice near its critical probability pc. That is, θ(p) ≈ (p - pc)5/36 for any planar lattice. This is an indication of universality, the hypothesis, based on physical reasoning, that there are critical exponents, such as 5/36, that depend only on the dimension and not on the details of the particular lattice.

In fact, it has been mathematically verified, by Lawler, Schramm, and Werner, that, for site percolation on the triangular lattice, θ(p) has this form. At present, however, we are not able to say that this result holds more generally.

Other, similar results hold as well. If we consider χ(p), the average number of vertices in C0 when p < pc, physics tells us that it should be true that

Also, suppose that p = pc and consider P(n ≤ |C0| < ∞), the probability that the cluster containing the origin contains a finite number of vertices greater than or equal to n. Physics again predicts that

|

P(n ≤ |C0| < ∞) ≈ n-5/91.

|

Both of these power laws have been proven for site percolation on the triangular lattice by the work of Kesten, Lawler, Schramm, Smirnov, and Werner.

At this time, it appears that theoretical physics, more specifically, conformal field theory and quantum gravity, have a great deal to say about percolation. One of the challenges before mathematicians is to create a mathematically rigorous theory to support these physical insights by, in particular, verifying conformal invariance for percolation on two-dimensional lattices and the universality of power laws.

Mathematics has traditionally been tightly connected to physics. It is interesting to see that the link between these two disciplines is still so vital. The mathematical importance of this field is demonstrated by the fact that Wendelin Werner was awarded mathematics' highest honor, the Fields Prize, in part for his work in percolation.

References

- Béla Bollobás, Oliver Riordan, Percolation, Cambridge University Press. 2006

- Geoffrey Grimmett, Percolation, Second Edition. Springer. 1999

The above are two excellent references from which I have borrowed heavily.

- Harry Kesten, What is ... Percolation?, Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 53 (5), May 2006. 572-573.

A short, readable survey.

- S.R. Broadbent, J.M. Hammersley, Percolation processes. I. Crystals and mazes. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 53, 1957. 629-641.

Broadbent and Hammersley's original paper.

- T.E. Harris, A lower bound for the critical probability in a certain percolation process. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 56, 1960. 13-20.

- H. Kesten, The critical probability of bond percolation on the square lattice equals 1/2. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 74, 1980. 41-59.

- R.P. Langlands, P. Pouliot, Y. Saint-Aubin, Conformal invariance in two-dimensional percolation, Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 30, 1994. 1-61.

- S. Smirnov, W. Werner, Critical exponents for two-dimensional percolation, Mathematics Research Letters, 8, 2001. 729-744.

- Fields Medal Citation for Wendelin Werner

David Austin

Grand Valley State University

david at merganser.math.gvsu.edu

Those who can access JSTOR can find some of the papers mentioned above there. For those with access, the American Mathematical Society's MathSciNet can be used to get additional bibliographic information and reviews of some these materials. Some of the items above can be accessed via the ACM Portal , which also provides bibliographic services.

This path moves through another vertex v1. The probability that an open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below passes through v1 is pPn-1, the probability p that the edge from v0 to v1 is open times the probability Pn-1 that a path from v1 to a vertex n - 1 levels below it is open. Therefore, the probability that there is no open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below passing through v1 is 1 - pPn-1.

This path moves through another vertex v1. The probability that an open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below passes through v1 is pPn-1, the probability p that the edge from v0 to v1 is open times the probability Pn-1 that a path from v1 to a vertex n - 1 levels below it is open. Therefore, the probability that there is no open path from v0 to a vertex n levels below passing through v1 is 1 - pPn-1.

Consider the figure to the left, in which we have two squares of sides n and 2n. Consider the event F1 described by a configuration of open paths, like the blue and red ones shown below. We know that the probability of an open vertical path in the smaller square is greater than 1/2. In the same way, the probability of having a horizontal path, like the red one, open is greater than 1/2 as well. The fact that we want the red path to enter the smaller square introduces another factor of 1/2:

Consider the figure to the left, in which we have two squares of sides n and 2n. Consider the event F1 described by a configuration of open paths, like the blue and red ones shown below. We know that the probability of an open vertical path in the smaller square is greater than 1/2. In the same way, the probability of having a horizontal path, like the red one, open is greater than 1/2 as well. The fact that we want the red path to enter the smaller square introduces another factor of 1/2:

Now let F2 be the event that there is an open path across a 3n by 2n rectangle. We break this into smaller pieces by considering the rectangle to consist of two squares of dimension 2n by 2n overlapping in an n by 2n rectangle. Applying our previous result, we have

Now let F2 be the event that there is an open path across a 3n by 2n rectangle. We break this into smaller pieces by considering the rectangle to consist of two squares of dimension 2n by 2n overlapping in an n by 2n rectangle. Applying our previous result, we have

Continuing in this way, we may continue to understand wider rectangles by breaking them into smaller rectangles that overlap in a square. For instance, the figure to the right illustrates an argument showing that the probability there is an open path across a 2n by n rectangle is greater than 2-15.

Continuing in this way, we may continue to understand wider rectangles by breaking them into smaller rectangles that overlap in a square. For instance, the figure to the right illustrates an argument showing that the probability there is an open path across a 2n by n rectangle is greater than 2-15.

/2), and P'3 = (0, 0). Now the fourth point P4 corresponds to a point P'4 = (x, 0) as shown below.

/2), and P'3 = (0, 0). Now the fourth point P4 corresponds to a point P'4 = (x, 0) as shown below.